Many believe that migration has had a limited impact on population trends in Europe so far. But Chris Wilson and his co-authors demonstrate that, for many countries, migration is already a key factor that has prevented population decline in low fertility countries.

The debate over dropping fertility and role of immigration

Both national governments and the European Commission have highlighted Europe’s low fertility levels as a challenge to long-term social and economic sustainability. Demographers have devoted considerable efforts to explaining why the birth rate is so low and what might be done to raise it. Migration as a solution remains a contentious topic in many countries. That discussion ignores the impact that migration already has on existing population trends within most European countries. It also highlights the lack of a clear definition of how migration may compensate low fertility levels.

A clear way to measure migration's impact

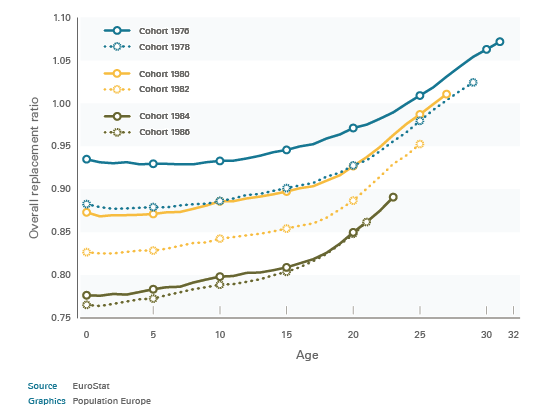

To provide a more systematic assessment of population replacement in different parts of Europe, the researchers develop a simple and effective measurement. It sets the size of a female birth cohort in relation to the average number of mothers in that year. The resulting number is defined as the overall replacement ratio (ORR). As the cohort ages, changes of this ORR can be tracked (see figure 1). The scientists focus on the first three life-decades, because at that age, mortality is a negligible factor. Therefore any change in the ORR can only be due to migration.

Figure 1: Overall replacement ratio by age for the EU-15 (minus Ireland), cohorts 1976-1986]

As expected, these cohorts all start of with an ORR below the replacement level. However, after the age of fifteen, there is a clear upward trend for all of them. By the time they reached their mid-twenties, a positive migration-balance helps them to match or exceed replacement level.

What's being debated is already happening

The scientists also take a closer look at the developments in the different European countries (see Table 1). Whilst the overall pattern is similar to the one for the EU15, certain variations can be directly linked to specific migration events in the countries history. For example the large rise in each cohort in Germany in the early 1990s indicates the influx of refugees from former Yugoslavia.

However almost everywhere in Western Europe, data on women born during the 1975-1980 period of declining fertility shows that by the time this cohort reached age 28, the ORR was close to or above the replacement level.

Table 1: Overall replacement ratio at ages 0 and 28 in female birth cohorts 1975 and 1980, in specified European countries and for the EU-15, excluding Ireland

As significant numbers of immigrants are older than 28, a further rise in the ORR is likely to occur after that age. Therefore the authors strongly suggest that projections of Europe’s imminent demographic demise are far from realistic. In much of Europe it is manifestly clear that, while the idea of replacement migration, as proposed by the United Nations in 2000, has been widely criticized, in reality this is precisely what is happening.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.