by Amparo González-Ferrer

Spanish emigration has captured headlines in recent years. It is understandable considering how historically emotive the phenomenon has become in a country so many were forced to leave throughout the 20th century. But the situation of Spain’s own immigrant population also deserves some reflection.

We know that immigrants suffer worse levels of unemployment than Spain’s native population. They end up in the most precarious sectors, have less resilient social networks, and are legally vulnerable to discrimination. The government’s 2012 privatisation of healthcare for foreigners in an irregular situation further complicates their lives in Spain. So at a time when Spaniards themselves have been leaving, why have many immigrants stayed put? Given the circumstances, it seems logical to assume that many will choose to leave Spain, if they haven’t already done so. Perhaps this was even the hidden logic behind such socially harmful policies that obviously cannot be justified by the budget.

Figure 1 clearly indicates that the crisis accentuated the rate at which foreigners left Spain, peaking for all groups except immigrants from the EU’s richest countries (EU-11) in 2013. Between 2008 and 2013, the rate at which Latin Americans returned home doubled. The rate for EU citizens multiplied by 1.7, whether or not Bulgarians and Romanians are included. This rate was matched by Asians.Emigration of foreign-born residents per 100 registered of the same origin at the beginning of the year by nationality, 2008 -2014. Source: Source: Statistics of Migrations and Municipal Inhabitant Registries, INE. NOTE: EU-11 includes Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, the UK, and Sweden. These countries selected are those already disagregated in INE data for UE-15 countries.

Figure 1: Emigration of foreign-born residents per 100 registered of the same origin at the beginning of the year by nationality, 2008-2014.

Source: Statistics of Migrations and Municipal Inhabitant Registries, INE. NOTE: EU-11 includes Belgium, Germany, Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, the UK, and Sweden. These countries selected are those already disagregated in INE data for UE-15 countries.

Not Particularly Surprising

Yet while these hikes are significant, they are not particularly surprising considering the magnitude and duration of the economic crisis in Spain. Furthermore, it is not clear whether the rise in unemployment necessarily drove people to return as originally predicted, or at least not immediately. Africans are the most paradigmatic example. While the employment rate of African women and men fell 15% and 30% respectively between the end of 2007 and the end of 2010, their combined rate of emigration from Spain in the same period rose by only 24%, notably below the average of 28% for all of Spain’s immigrants and far below the 34% of Latin Americans or the 38% of EU-11 immigrants.

Even if we consider the period 2008 to 2013, the emigration of Africans has risen least during the crisis—50%, compared to 75% for all groups combined and 105% for Latin Americans—despite being the group most affected by unemployment and precarious working conditions.

Estimates calculated in 2008 predicted that between 20% and 50% of all immigrants in the OECD would leave their host country in the following five years. While the data in Spain do not allow us to make calculations based on arrival cohorts, they suggest a rate of return well inside the margins of these estimates—about 49% for the whole period.

Resistance to Return

In other words, we could speak of a certain resistance to return, at least as a first and immediate reaction to worsening economic conditions.

What could explain this resistance? Surely, the same that explained their original emigration: the indomitable desire to find a better life for themselves and their own. In fact, it seems that the number of immigrants that continue to consider Spain a good place for their families is quite high. In a 2011 survey of adolescents and their parents in Madrid**, 69% of the parents confirmed that they would like their children to live in Spain as adults. Among their motives they cited first and foremost their conviction that Spain was a country that offered more opportunities for a future than other countries and, accordingly, the idea that Spain was a good country for the quality of life it offered.

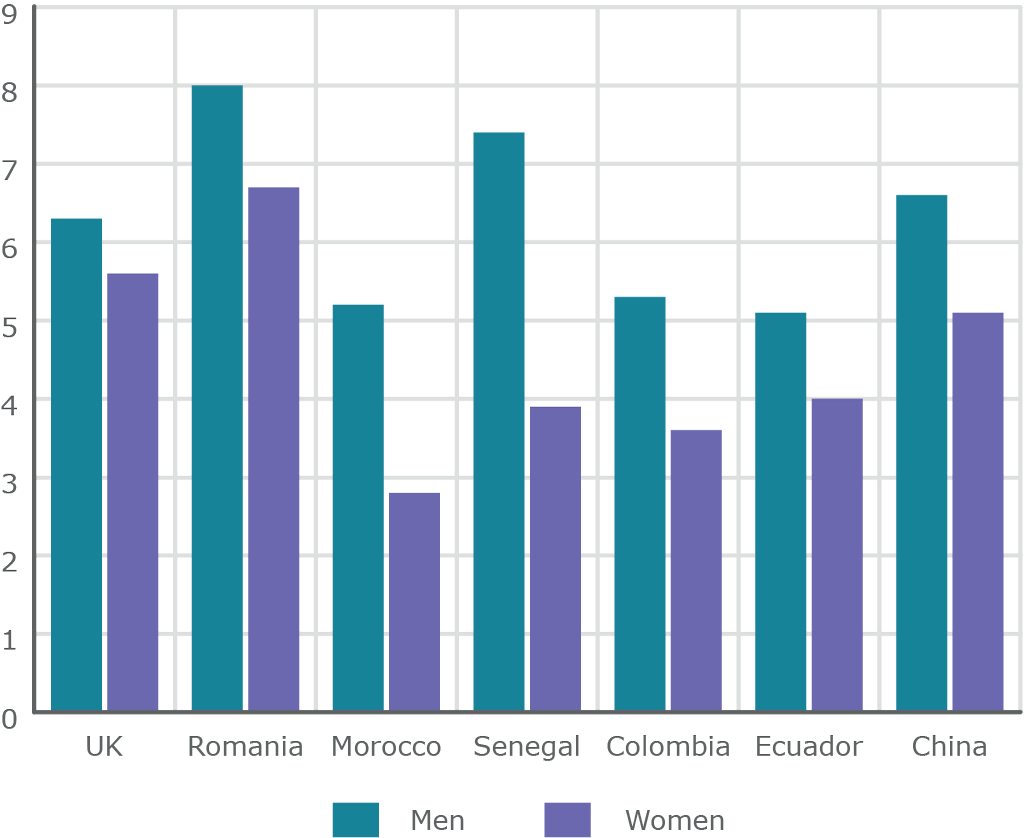

These desires make sense of the differences between sexes and age groups observed in registry data (Figures 2 and 3). In particular, we see immigrant women—in general less affected by unemployment than men and always more likely to have brought their children—are less likely to have left. This is the case in several groups.

Figure 2: Annual exits per 100 registered by sex and nationality, 2014.

Source: Statistics of Migrations and Municipal Inhabitant Registries, INE.

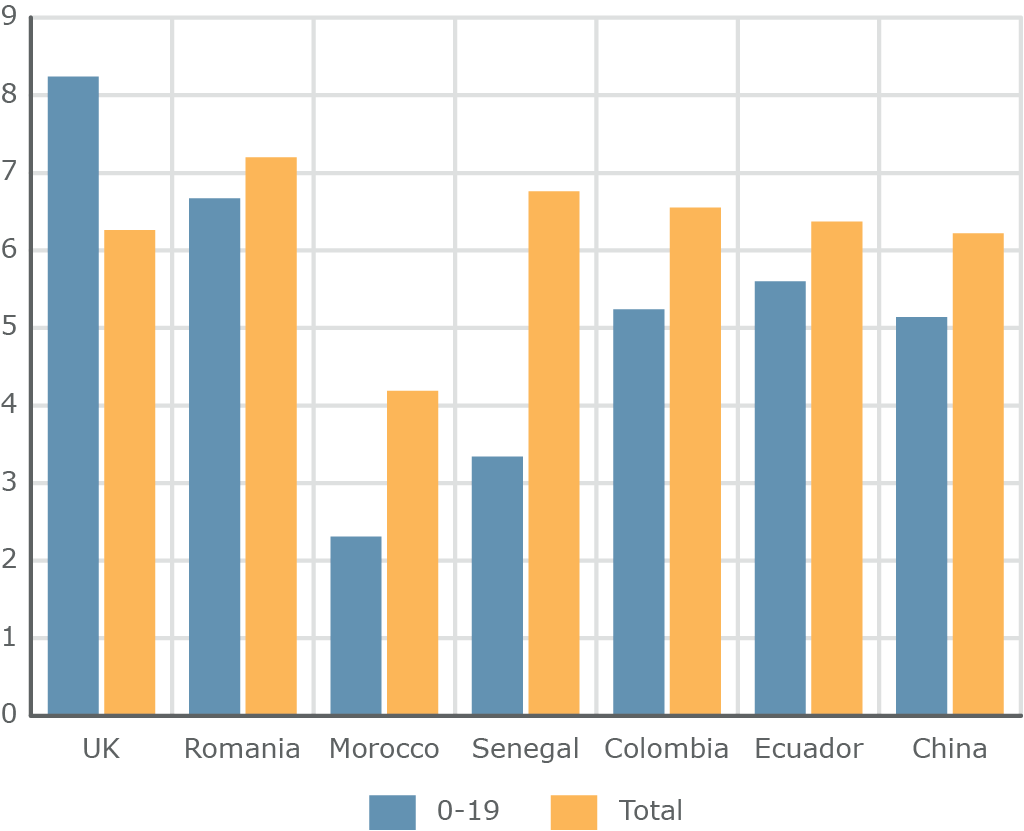

Figure 3: Annual exits per 100 registered by age group and nationality, 2014.

Source: Statistics of Migrations and Municipal Inhabitant Registries, INE.

We also find that the youngest—those younger than 20—abandon Spain much less frequently than the rest, as suggested by figure 3. This seems to confirm the idea that already-unified families with their children in Spain resist return more intensely. The dizzying rate at which families were united before the crisis (80% of couples and 60% of families with children under 18) has essentially modified the logic and timing of returns. We find that it is no longer only a question of work, but also of children, their school where they have friends, or a partner’s job. A return involves a plan for everyone, tickets for everyone, and everyone’s friends. Foreigners, like Spaniards, resist abandoning a country where they have planted roots, where they have worked, where they have acquired homes, and where they have raised their children.

They resist leaving a country that is also theirs.

By 2012 we began to detect a moderation in the differences between men and women and between minors and adults. This suggests that, also like Spaniards, the crisis and its persistence have begun to provoke and even defeat the most defiant—those who were without a doubt the most and best integrated.

Which begs the question: what kind of returns are we favouring?

* The content of this post is the fruit of the research undertaken as part of the TEMPER Project (Temporary versus Permanent Migration)

An earlier version of this post was published in Spanish in the blog Piedras de Papel

**Survey carried out under the auspices of Project Chances, which is financed by CEACS of the Juan March Foundation, CSIC, and the Spanish Ministry for the Economy and Competitiveness. It is directed by Amparo González-Ferrer and Héctor Cebolla-Boado. Its data will be publicly available in 2017.

About the author:

Amparo González-Ferrer, Senior Research Fellow at the Spanish Research Council (CSIC) and Coordinator of the TEMPER Project.