Though it may not be a silver bullet to solve workforce shortages, the migration of highly-skilled individuals around the world is recognised as an important driver of productivity gains, innovation, and entrepreneurship. This motivates governments of EU member states, including the Netherlands, to consider policy changes in order to help attract “knowledge migrants”. In a recent study, Anu Kõu, Leo van Wissen and Ajay Bailey evaluate what drives highly-educated professionals to migrate to the Netherlands. Their results indicate that so-called “knowledge migration” depends on more than just attractive jobs.

In particular, the researchers from the Population Research Centre of the University of Groningen argue that the importance of high salaries and other economic advantages in receiving countries tends to be overrated. Policies aimed at luring the most highly-skilled migrants should instead adopt a more comprehensive approach. They should pay attention to migrants’ cultural backgrounds, their norms and values, their earlier life experiences and their future expectations concerning career options, as well as family formation.

Knowledge and talent migrants in the Netherlands

Striving to be one of the pioneers in the EU knowledge economy, the Dutch government introduced a special visa in 2004. Migrants with nationally or internationally scarce specialised knowledge and an above-average income are eligible for a work visa according to the duration of their work contract, for a maximum of five years. After that, they can apply for a permanent residency permit. The professionals may be accompanied to the Netherlands by their spouses and children, who can obtain residence and work permits there with minimal bureaucratic hassle.

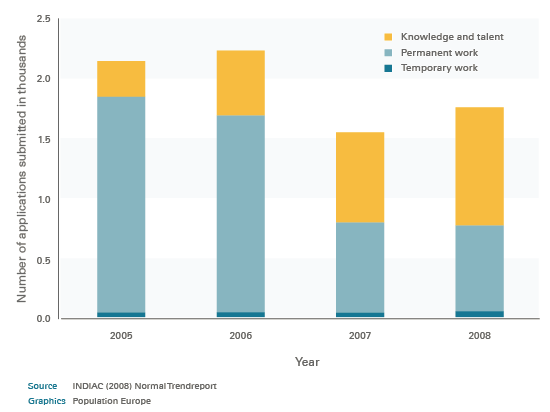

This visa has proved quite successful (see figure 1): The number of applications submitted by highly-educated labour migrants to the Netherlands rose from about 3,000 in 2005 to about 10,000 in 2008. This corresponds to an increase in the share of talent and knowledge migrants among all labour migrants from 15 to almost 50 percent.

The typical knowledge migrant in the Netherlands is young and male, originates from India (30 percent), China, Japan or Turkey and works in the ICT sector or other business services (30 percent), or in the industrial sector (13 percent). Only 8 percent are employed in education and research, which is quite a low figure given the Lisbon and Barcelona agreements aimed at encouraging international exchange in these areas.

Linked lives: the importance of family and friends

The decision to migrate has a significant impact on other aspects of the life-course and vice versa. On one hand, those willing to migrate might get married earlier than they would have otherwise, in order to take advantage of visa spousal accompaniment provisions, or, on the contrary, get married at later ages than their non-migrant counterparts in order to first settle down in their job abroad. On the other hand, parenthood may be postponed. Some of the factors that foster or inhibit migration are hence strongly related to the situation of family members and friends.

Informal networks also play a crucial role in helping potential migrants to become aware of career and work opportunities abroad, and seem as important in this regard as support by professional organisations. Moreover, they can provide immaterial support in the country of destination. These “soft factors” can guide both the decision of whether or not to migrate and where exactly to go.

Therefore, an enhanced understanding of these networks of “linked lives” can help those countries that wish to attract knowledge migrants more effectively shape their informational campaigns, as well as their material and immaterial support programmes.

Figure 1: Applications for a first residence permit submitted after the introduction of the special visa for ‘knowledge migrants’, 2005 – 2008*

*(First 6 months of 2008)x2

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.