During the last hundred years, divorce and separation rates have increased dramatically in all European countries. But does it mean the same for children and adolescents today as it did a century ago? How has the association between parental divorce and child well-being changed in magnitude over time? To answer these questions for Sweden, Michael Gähler and Eva-Lisa Palmtag use six waves of the Swedish Level of Living Survey, and explore data on childhood living conditions for an entire century of Swedes, born between 1892 and 1991.

Serious Conflicts

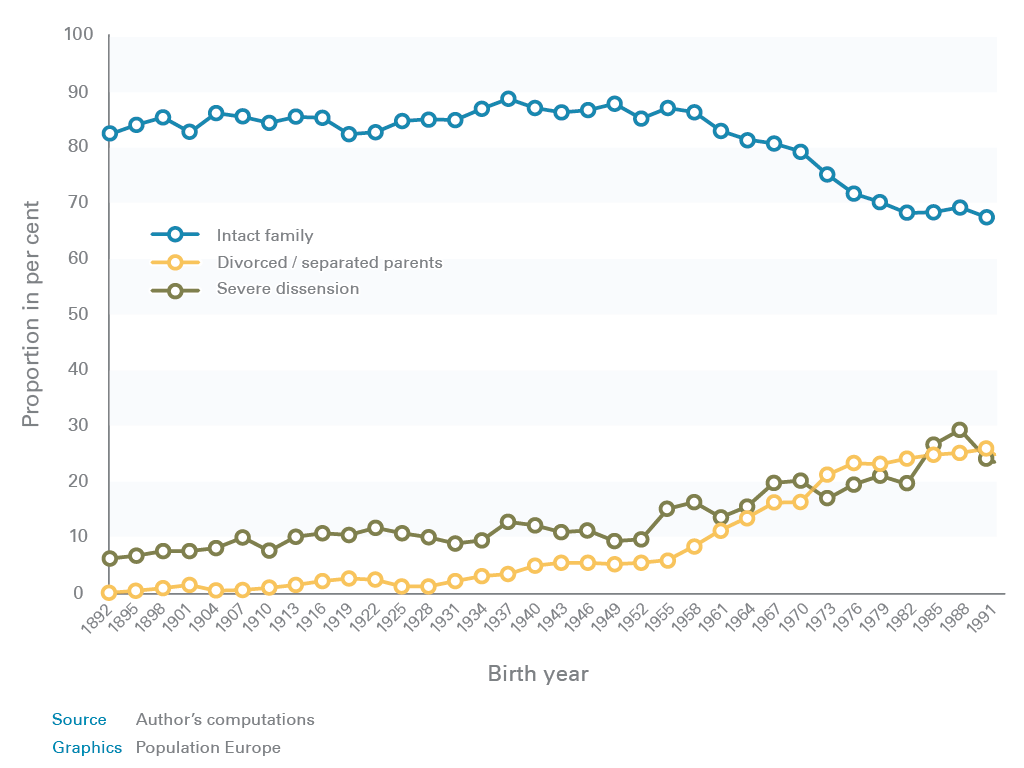

According to the data, the proportion of children and adolescents who experienced family dissolution before age 16 has increased from around one per cent of those born in the late nineteenth century to around one-fourth of those born one century later. The proportion of respondents reporting serious conflicts in their childhood family has increased from almost 10 per cent to approximately one-fourth (Figure 1). For a long time, for respondents born from the 1890s to the 1950s, there was a gap between parental divorce and domestic conflicts: It was clearly more common for children to experience parents arguing than to experience divorce. This implies that many parents continued to live together although their relationship was characterized by severe conflicts.

Figure 1: Childhood family type and severe dissension in the childhood family by birth year (1892-1991). Five years moving averages.

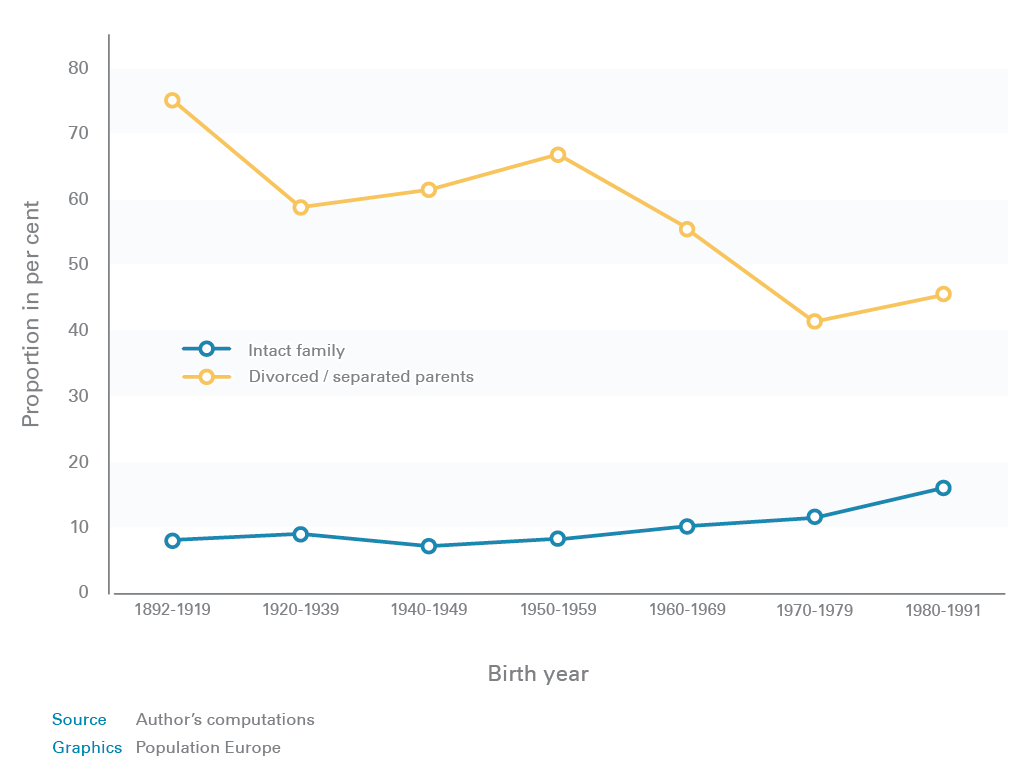

Early in the period, almost every eight in ten respondents from dissolved families report serious conflicts in their childhood family (Figure 2). This proportion is considerably lower, less than half, for cohorts born between 1970 and 1991. This development accords with changes in divorce motives over time. Previously, when divorce was socially stigmatized and the economic and legal obstacles were higher, spouses were often forced to stay together and only divorced if the situation was unbearable. During the twentieth century in Sweden, social stigma associated with divorce and separation declined and an almost constant economic growth and the introduction of welfare state arrangements improved living conditions in general, lowering obstacles for divorce.

Figure 2: Severe dissension in childhood family by childhood family type and birth year (1892-1991).

New Circumstances

Thus, the separation of parents today is associated with other circumstances and living conditions than it was a century ago. A smaller proportion of respondents with divorced parents claim to have experienced severe family conflicts and economic difficulties in their childhood. At the same time, divorce has become more common across all classes, the working class in particular, so there is less social stigma connected to it. Increased numbers of children stay in contact with the non-custodial parent, experience residential mobility and reconstituted families.

The results also suggest that there is no direct link between parental divorce in childhood and psychological well-being in adult age. When observed, a lower psychological well-being among adult children from dissolved families seems to be associated with the fact that they were more likely to experience economic difficulties and severe conflict in their childhood family. For education, matters stand partly different: Severe conflict in the childhood family is not associated with low education as an adult and, therefore, cannot explain why respondents from dissolved families are less likely to attain a high level of education than respondents from intact childhood families. However, individuals from dissolved families are more likely than previously to have low educated parents belonging to the working class, and the relative difference in economic difficulties during childhood has increased during later decades, to the disadvantage of these individuals’ school attainment.

The basic association between childhood family type and both education and psychological well-being as an adult, however, has remained unchanged over time. Remaining, if not increasing, family type differences in family conflict and economic conditions have a strong impact here, as previous American and British studies already suggested. As long as these differences remain, we should expect little change in the association between individuals’ experience of parental divorce in childhood and their adult well-being.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

*This PopDigest has received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 320116 for the research project FamiliesAndSocieties.

FamiliesAndSocieties (www.familiesandsocieties.eu) has the aim to investigate the diversity of family forms, relationships and life courses in Europe, to assess the compatibility of existing policies with these changes, and to contribute to evidence-based policy-making. The consortium brings together 25 leading universities and research institutes in 15 European countries and three transnational civil society organizations.