Europe’s population is getting older and older and this process is accompanied by many economic and social changes. The necessity of modifying pension systems and increasing the pension age are among the most discussed of these changes at the moment. Britain's the Netherlands’, Germany’s, Denmark’s and Spain’s national pension age will increase to 67. Ireland's pension age will even rise to 68. But how can policy makers justify to public those increases in pension age? How will they know how many of the “last years” are likely to spend in good health? Researchers Warren C. Sanderson and Sergei Scherbov suggest new methods to evaluate life expectancy. Their model looks at the health conditions of individuals – with surprising results.

Remeasuring Ageing

So far, data about life expectancy were mainly based on “conventional measures of ageing”. The usual tool was the “old age dependency ratio” (OADR), which assumes that people are dependent on others when they reach the age of 65. There is now a more precise measure. Not only do people get older, they also stay healthy and independent longer. In other words, increasing life expectancy also means gaining healthy years and not automatically becoming a burden on the health care system. This is why indicators must include more factors, such as a disability rate.

Alternative Calculations

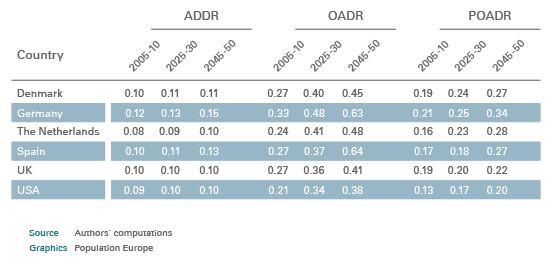

The first alternative to the OADR is the “prospective old age dependency ratio” (POADR). It takes forecasted increases in life expectancy into account and is defined as the number of people in age groups with life expectancies of 15 years or fewer, divided by the number of people aged 20 years or older in age groups with life expectancies greater than 15 years. As seen in Table 1 the POADR increases less rapidly than the OADR.

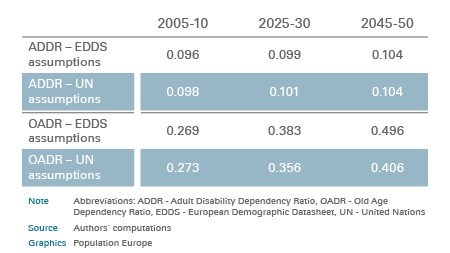

Specific disability rates in certain age groups have decreased enormously. In the US, the proportion of people with a disability in the age group 65 to 74 declined from 42% in 1982 to 8.9 % in 2004-05. Considering those developments, conventional measurements do not evaluate the effects of age structure well. To investigate the effects of disability, the authors define a measure analogous to OADR. It is called “adult disability dependency ratio”(ADDR) and is defined as the number of adults at least 20 years old with disabilities, divided by the number of adults at least 20 years without them (see Table 2). The ADDR is rather robust and could therefore limit the scope for political speculation and controversy.

Table 1: Forecasts of adult disability dependency ratios, old age dependency ratios, and prospective old age dependency ratios

Different and Less Disconcerting Calculations

Accordingly, the OADR rise much faster than the ADDR. In the UK, for example, the OADR increased from 0.27 in 2005-10 is expected to rise up to 0.41 in 2045-50. In contrast, the ADDR stays constant at 0.10 (See Table 2). Therefore, although the British population is getting older, it is also likely getting healthier and these two effects offset one another. Not only does the ADDR increase less rapidly than the OADR, it also increases less rapidly than the POADR. However, there are still a few problems with those data. There is a risk of omitting older people with disabilities, for example, if people in nursing homes are not included. Still, the ADDR takes into account the fact that people stay healthy much longer than they did in the past.

Table 2: Old Age Dependency Rates and Adult Disability Dependency Rates for the UK

Abbreviations: ADDR – Adult Disability Dependency Ratio, OADR – Old Age Dependency Ratio, EDDS – European Demographic Datasheet, UN – United Nations

Public Acceptance of Consequences

The improvements in health and longevity will not cease and politics and society will have to deal with these. Such new measures can help educate the public about likely consequences. To avoid reductions in future pension payouts most countries will likely increase pension ages even further. But slow and foreseeable changes in pension systems are justified by an equivalent gain in the number of healthy years spent in older age and therefore should be more politically acceptable. Population ageing will definitely be the source of many challenges in coming decades. Nevertheless, if one uses outdated measurements, negative effects of population ageing for the welfare state are exaggerated. With a larger array of measures we will be able to address these problems better.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.