Sweden is often referred to as a role model when it comes to gender equality in general, and for its parental leave allowances in particular. Ann-Zofie Duvander (Stockholm University) and Mats Johansson (Swedish Social Insurance Agency) aim at determining the effects of three reforms introduced in Sweden between 1995 and 2008 on the division of parental leave days between the parents. Sweden first introduced parental leave with earnings-related benefits in 1974. The length of leave was extended in the 1980s to over a year.

Three reforms between 1995 and 2008

A first reform aiming at a gender equal leave use was realised in 1995: One reserved month for each parent was introduced, which meant that this month would be lost if not used by the designated parent (so called “daddy and mummy months”). A similar reform had been introduced in Norway a year earlier. Both were considered radical at the time.

Another month for each parent came in 2002. In addition, one month was added to the general leave length, resulting in an overall leave duration of 16 months. This meant that an increase in one parent’s leave did not necessarily entail a decrease in the other’s leave. In 2008 Sweden’s liberal conservative government introduced a gender equality bonus. The reform implies that the more the leave is shared between the parents, the greater the bonus they receive. Also this reform is gender-neutral but as mothers traditionally use more leave than the father the bonus encourages women to shorten their leave and men to extend their leave.

Measuring the effects

All three reforms aim to motivate parents to divide parental leave but with different means. For policy makers it is of crucial interest to find out the effectiveness of different reform types. To measure the effects of the three reforms on the division of leave, Duvander and Johansson analysed them at the same point in time with the same sample selection and control variables.

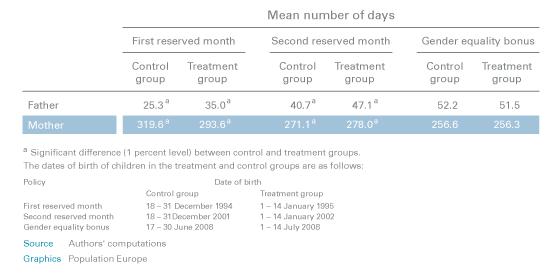

Table 1 shows the average use of parental leave days during the child’s first 24 months for parents to children born just before and after the reforms. By sampling parents to children born just before and after (control and treatment group) the introduction of the reform the authors eliminate the risk that some parents steer their childbearing in relation to the reforms. In this way the direct and causal effect of the reforms are measured. The results show that the first reform in 1995 clearly had the largest effect on both fathers’ and mothers’ use. The fathers’ use increased from an average of about 25 days before the reform to 35 days just after the reform. Conversely, mothers’ use of leave decreased. Also, the introduction of the second reserved month shows a visible effect on fathers’ use of parental leave, on average seven days increase. As the leave is extended at the time also mothers’ use increased. In contrast, the gender equality bonus apparently did not lead to any statistically significant changes in either mothers’ or fathers’ use of parental leave.

Table 1: Mean Number of Days / Comparison

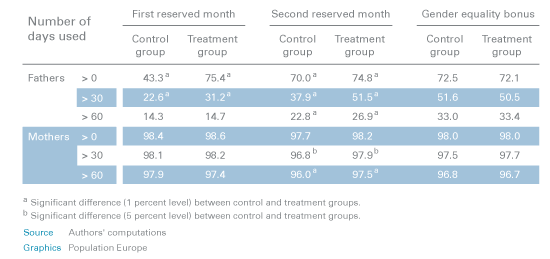

Table 2 presents the proportion of fathers and mothers with children born just before the implementations (control group) and after (treatment group) with different levels of use. Here again, the first reform shows a major impact: the amount of fathers making use of parental leave increased dramatically from two-fifths to three-quarters of all fathers. The second month instead increased the proportion of fathers using about two months of leave. But the most recent reform did not have any direct effect.

Table 2: Comparison Mothers / Fathers

Learning from Sweden?

It seems that the first reform had more impact on leave use than the two later reforms. The gender equality bonus did not seem to have any effect on parental leave and it is possible that it was too complicated and not sufficiently transparent. It may also be that it is more difficult to change the leave use of fathers at higher levels of use.

However, there is a trend towards increasing the duration of parental leave for fathers and somewhat decreasing leave length for mothers in the Swedish Society. So even if the mentioned reforms have a positive impact on this trend, they are not the only reason for fathers’ increased leave use. Instead one could consider reforms accelerators in an ongoing process.

Duvander and Johansson consider it difficult to determine whether the Swedish system could serve as a model for other European, since the results are likely dependent on other contextual factors, such as a broad availability of daycare and strong labour market protection for parents.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This Population Digest has been published with financial support from the Progress Programme of the European Union in the framework of the project “Supporting a Partnership for Enhancing Europe’s Capacity to Tackle Demographic and Societal Change”.