The measurement of human longevity is one of the most important topics in demography. This includes not only how long people live, but also how long they expect to live. To underestimate your lifespan could cause risks in individual retirement planning. A realistic view of life expectancy may also contribute to the acceptability of policies that attempt to increase the pension age. However, there have been only a few representative studies on how long people expect to live. Researcher Alison OˆConnell reviews the available evidence.

Subjective lifespans

How does the population view longevity? How long do they expect to live? The so-called “lifecycle savings hypothesis” determined that people did not save enough money for retirement because they underestimated their lifespans. There were also more detailed analyses about whether people were saving enough money for specific “retirement goals”. All these researches found some evidence of “undersaving”, but they are also based on highly complex calculations with many controversial assumptions. Although these findings take the possibility of “undersaving” into account, they do not take into consideration the fact that expected lifespan is underestimated.

Another important aspect is the right term. “Life expectancy” is the most common term in demographic science; however, it uses the average mortality rate of a population, and not the subjective expectation of longevity. To avoid confusion, O’Connell uses the term “subjective lifespan” for individuals’ expectations regarding their own longevity. She finds that only six studies about how long people expect to live are representative of a national population. The overview shows that people tend to underestimate their total lifespan.

Gender, education-level, and self-reported health status play a role

According to the studies, men are aware that they generally have a shorter lifespan than women. Even so, they are much more optimistic than their female counterparts. Men underestimate their lifespan by four years, whereas women expect to live six years less. Alison O’Connell asks for the reasons. It is generally known that men live shorter lives than women, but how do subjective longevity expectations generally vary by mortality risk factors? Do people have lower expectations for their own longevity if they know about their higher mortality risk?

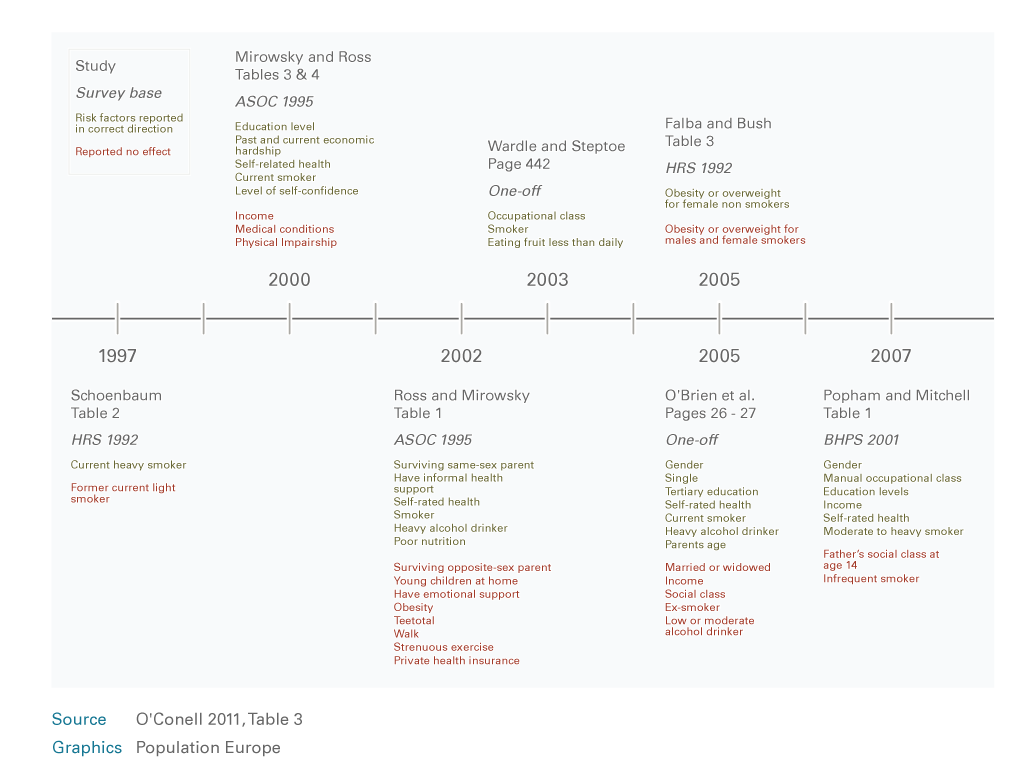

Table 3: Self-reported risk factors

More data available in the original article

One important factor seems to be “self-reported health status”. It was found to be directly linked with longevity expectations. If you feel healthy, you are more likely to expect to live a longer life. Another interesting aspect is that being overweight does not seem to have a large impact. If people are overweight, they do not generally think they would live a shorter life, although in actual fact, obesity is quite an important factor for a shorter life span. Smoking appears to have a stronger influence on subjective longevity expectations. Although smokers anticipate a shorter longevity than non smokers, they still tend to underestimate the real risks of smoking. Another statistical fact known by demographers is that education and socio-economic status plays a role in longevity. Well-educated people tend to live longer, as with those of higher socio-economic status. But because this is not as commonly known, longevity expectations tend to not reflect socio-economic factors as well as the role of education in affecting total lifespan. People tend to not consider it. O’Connell summarises: The most widely known risk factors appear to be gender, self-reported health status, and smoking. (Table 3)

Tendency to underestimate

All surveys assume that people have a general idea about their likely lifespans, but there is a common tendency to underestimate how long they will actually live. Therefore, policy makers can assume that people are not realistic about their longevity. They should be interested to know whether improving longevity is understood by the general population. Only if people are truly aware of how long they will probably live, they can act responsibly, for example, by saving money for a later time in life. More effort could be made to inform people that they can expect a longer lifespan and further research could develop more accurate knowledge by using larger and more representative samples.

Increasing the age of eligibility could send powerful signals about expectations for retirement age and length of retirement. The rise of pension age has been discussed a lot recently. If people are more aware of the fact that they will most probably live longer than they expect, it would most likely influence the debate positively.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.