"Population ageing is not only about older people," says Pearl Dykstra from Erasmus University Rotterdam in her article "Key Findings from the Multilinks Research Programme." Grounding their research on this key principle, Dykstra and her colleagues from Multilinks conducted innovative studies and brought forward new and unique insights on intergenerational relations in Europe.

Research frequently implies that demographic change affects mainly older people, their socio-economic status and well-being. Undeniably, one of the main demographic changes is an increasing proportion of older people, but population ageing also affects younger generations, and therefore attention should be devoted to all age groups, claims the author. A second key premise underlying the Multilinks research programme is that interdependencies should not be taken for granted but be examined in relation with legal and policy arrangements. Finally, Dykstra asserts that in order to better understand intergenerational relations, it is essential to differentiate between macro and micro levels, different regions, attitudes and behaviour, and policies and actual regimes.

Family changes

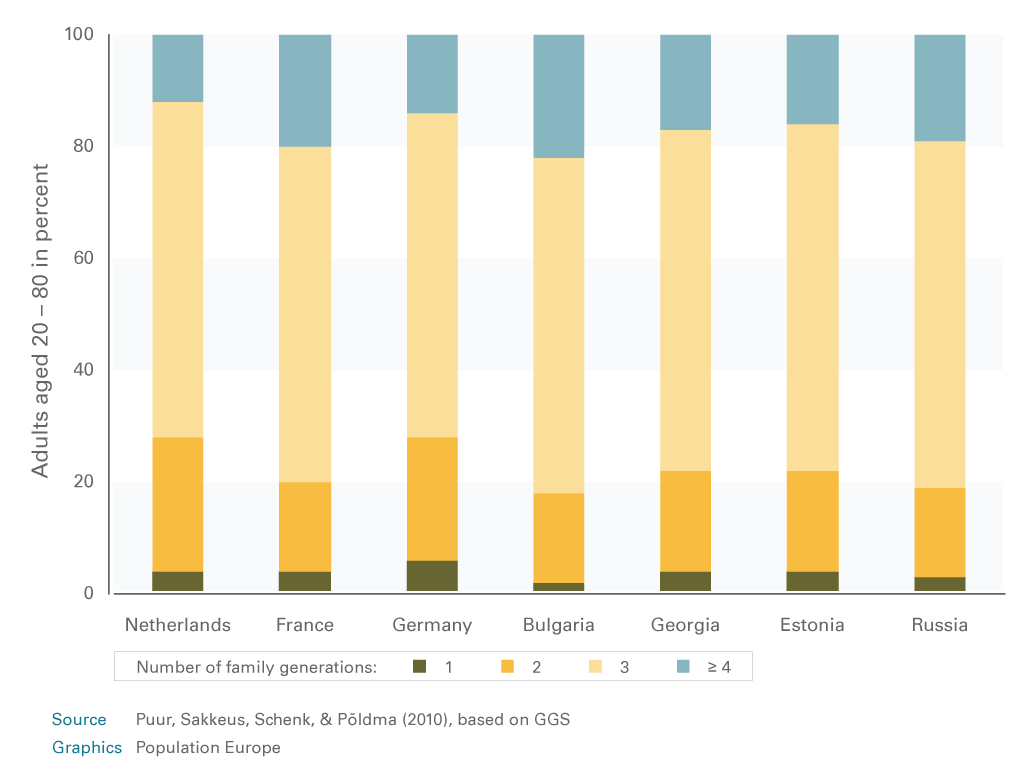

Previous research has shown that macro demographic changes led to verticalisation of family ties, where there are more vertical ties between parents, grandparents and great-grandparents than horizontal ties between siblings and cousins. Dykstra opposes this “conventional portrayal of family change” and suggests that three- and not four- or five-generation families are still typical in Europe (see Figure 1). By looking at the micro level, the author finds an explanation for this finding. It is rooted in the opposing effects of the increased life expectancy at birth and postponement of childbearing, and the differences in these indicators’ level of development between European countries.

Figure 1: Adults aged 20-80, by number of family generations, selected countries

A second myth regarding family change that Dykstra addresses is the metaphor of the sandwich generation. The author argues that adults classified as being the sandwich generation are between 30 and 60 years old. In this age range it is rather unlikely that people will have young children and frail parents in need of care simultaneously.

Lastly, the author stresses that a decrease in fertility means a decline in number of children per woman and does not necessarily lead to a severely lower number of children among mothers. A critical factor to consider is childlessness.

Living together – who helps whom?

Results from Multilinks show that when co-residence between generations exists, the young are more often those who receive help, and thus the direction of support is downwards from parents to adult children and not, as believed until now, vice versa. Using data from the Generations and Gender Survey, researchers in the Multilinks programme found that in less than 5% of households, older people are those who receive support. Additionally, parents become the recipients of support, most of the time, only at advanced age (>80 years).

Country and age specific policies – how important are they?

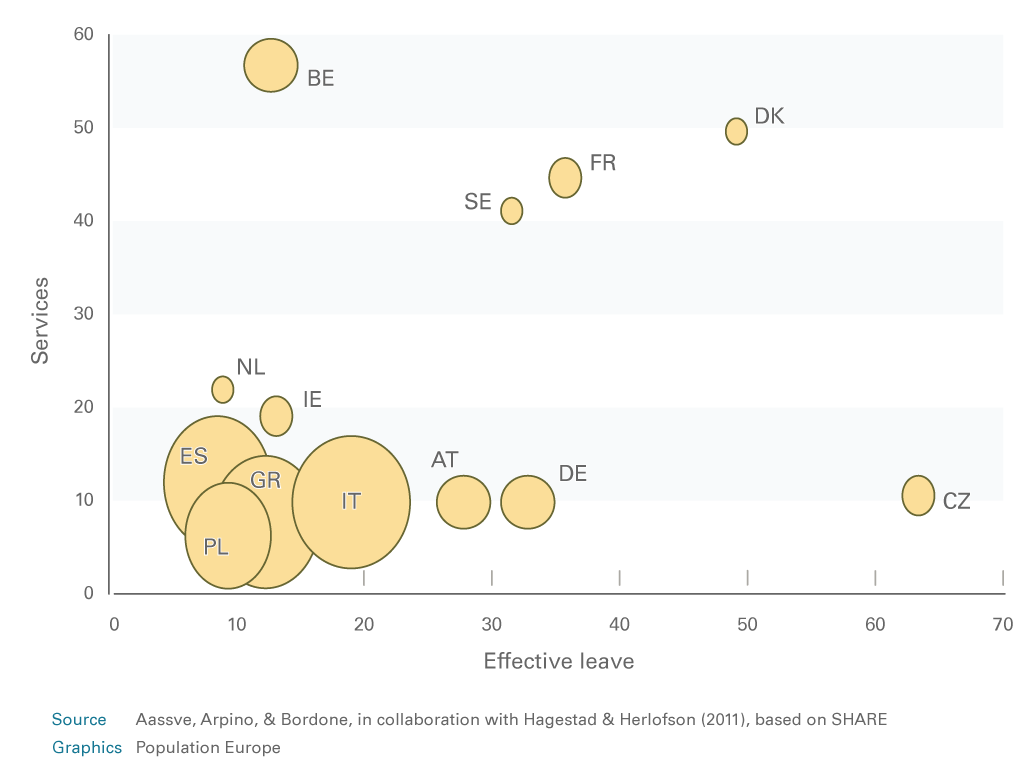

Building upon Survey of Health and Retirement in Europe data, studies within the Multilinks context show that country-specific policies influence family care. Dykstra presents the example of grandparenting in selected European countries and suggests that in states with the least generous services and leave provisions such as Spain, Italy, Greece and Poland, young adults most frequently rely on help with child care from their parents (see Figure 2). In addition, findings from their analysis of European Social Survey data provide evidence that being a grandparent accelerates retirement, particularly among older women. On the other hand, help provided with child care allows adult daughters to remain or re-enter the labour market.

Figure 2: Predicted probability of caring for a grandchild of a working daughter by level of effective leave and services

Finally, outcomes of the Multilinks project demonstrate that policies targeting specific age groups reinforce “compassionate ageism.” In other words, in countries with, for example, high child allowances, people seem to have more positive attitudes towards the young.

The final results of the Multilinks research programme disclose that the legal and policy arrangements in each country have an impact on intergenerational relations. Therefore, national policies, says Dykstra, “should seek to support intergenerational care regimes without reinforcing social class and gender inequalities.”

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.