European populations are shrinking in size every year. One reason for this is the decrease in births everywhere in Europe. However, within the overall declining trend, there are still huge differences between European countries when it comes to age at first birth and the number of babies per woman. Researcher Alícia Adserà is interested in finding out what accounts for those differences and what role unemployment rates and labour market conditions play.

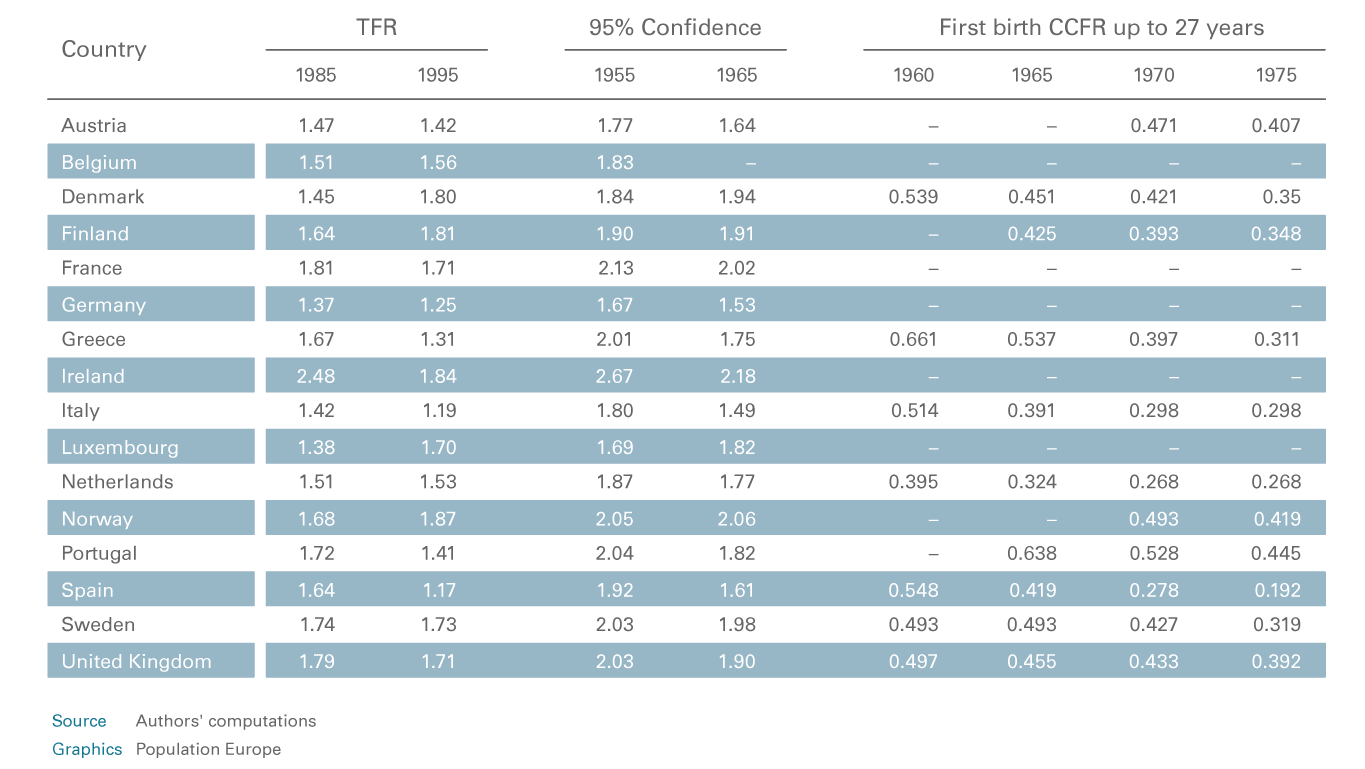

Since the late 1960s, the number of births has decreased everywhere in Europe. Currently, most countries, with the exception of Ireland, France and the Nordic states, have fertility rates well below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman (see Table 1). Fertility behaviour is the result of continuous and complex individual decisions. Those decisions may be affected by uncertain conditions and vary under different institutional and economic constraints. As a result there is a significant relationship between the economic environment and fertility.

Country Differences

Alícia Adserà from Princeton University attempts to find associations between country level unemployment, labour market institutions and fertility, as well as between the timing of motherhood and the changing economic environment. She also wants to determine whether these associations capture a significant portion of the declines in fertility. To do this, she used survey data of close to 50,000 women from 13 European countries. The statistical analysis aimed to measure the existing diversity of labour market arrangements and contracts across European countries. The covariates of interest comprised unemployment rates, shares of public sector and part-time opportunities. Additionally, all estimates included the country’s GDP per capita and maternity benefits.

Table 1: Period total fertility rate (TFR), total cohort fertility rate (TCFR) and first birth cumulated cohort fertility rates (CCFR) up to 27th birthday for selected cohorts and European countries

The Uncertainty of Unemployment

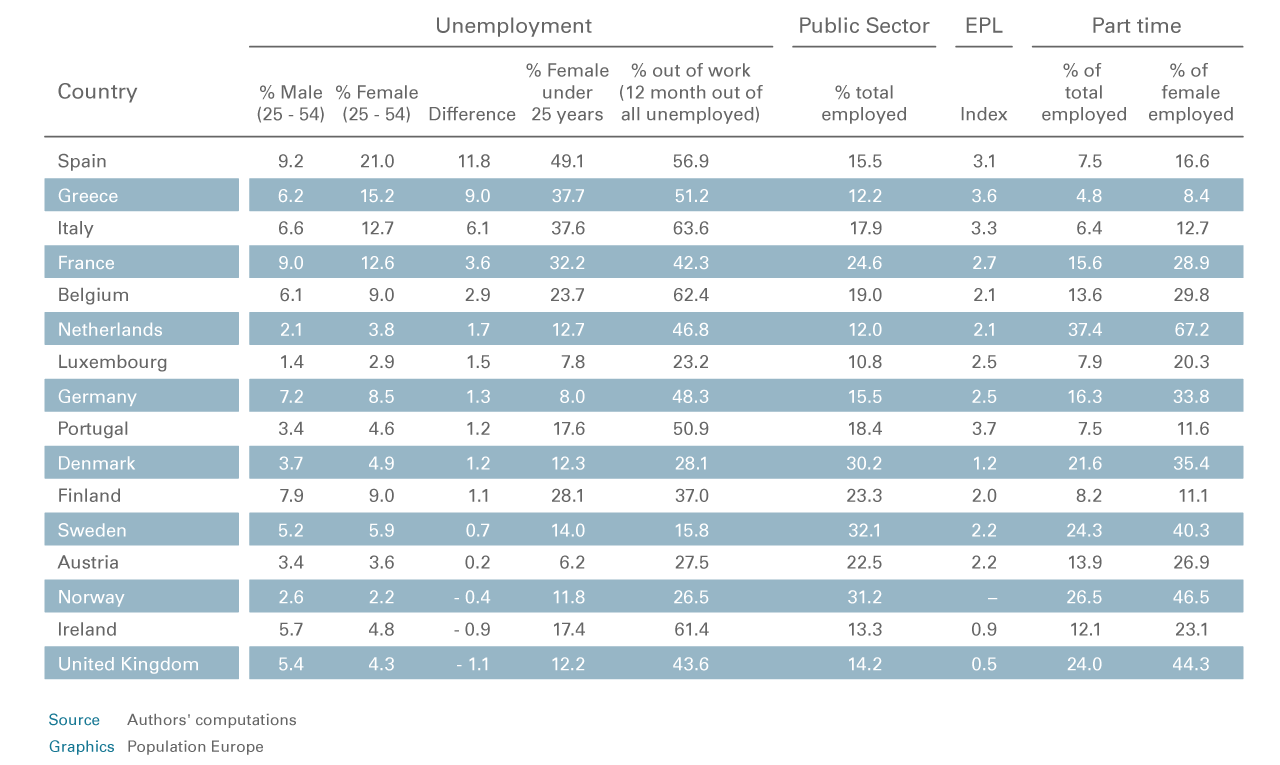

During the 1980s and 90s, there was a sharp increase in unemployment and uncertainty all over Europe, which is bound to have affected fertility rates. Adserà finds a clear and negative association of unemployment and fertility, regardless of the measure of unemployment used (total, female, youth or long-term unemployment) and even when controls for family friendly policies are taken into account. In countries where female unemployment is very low, around 5%, and not too persistent, almost two-thirds of women (64%) are already mothers at the age of 30. However, high and lasting unemployment in a country leads both to delays in childbearing and in second births. Barely 50% of women are mothers by age 30 in those scenarios. When a woman is unemployed early in life, she may postpone childbearing in order to invest more time in education and experience. She might also worry that the baby break may increase the possibility of future unemployment. Her partner may also be unemployed and, as a result, the available household resources may shrink. Additionally, in bad economic times parents may want to invest more intensively in education per child and therefore decide only to have one or two children. Somehow or other, the result is a decreasing number of children (see Table 2).

Table 2: Gender gap in unemployment rates, youth unemployment, long-term unemployment, prevalence of public employment and part-time employment and employment protection legislation (EPL) across European countries in the 1990s

Public sector and part-time possibilities

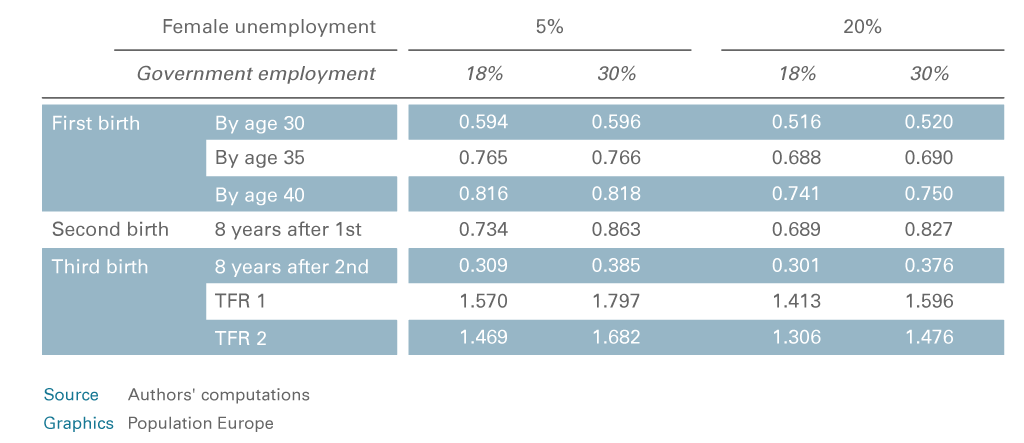

A large public employment sector generally does provide security and benefits and is therefore expected to be coupled with higher birth rates, particularly when it comes to the second and the third child. The differences in first births between countries with average government size and those with large public sectors are fairly small. But for the second and third births those differences are sizeable. Adserà explains this finding by noting that women still have to postpone motherhood until they have landed a secure job in the public sector. However, once they can benefit from the security that comes with the public sector position, they feel empowered to have more than one child (see Table 3).

Table 3: Predicted proportions of women transiting to births of different order according to country’s female unemployment rate and share of government employment

Not only working in the public sector, but also working part-time is positively associated with a second birth eventhough this association is weaker, especially if total household income is taken into account. The main effect of part-time employment is positive and significant in the model of transition to a second child. Adserà notes that women may initially aim for full-time positions and, later, once they are in a stronger bargaining position that protects them from losing their jobs, decide to work less due to their career-family demands. In the sample of European countries, women working part-time in the public sector after their first birth are the ones to have a second child the fastest among all mothers.

Conversely, women with non-permanent or temporary contracts, characterized by lack of tenure, reduced benefits, or stable earnings, are the least likely to give birth to a second (and third) child. This result is even more significant when the sample is restricted only to Southern Europe, where temporary contracts are most prevalent.

Less fear – more babies

Among other results, first births also occur faster when countries have more generous maternity benefits. When labour market institutions reduce uncertainties connected with childbearing, they make it easier to combine work and family and allow couples to better plan ahead. This certainly has an influence on fertility levels. Policies geared toward full employment, labour reforms that do not relegate the youngest to volatile contracts and laws that do not penalize part-time employment emerge as the most appropriate strategies to boost fertility.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.