As birth rates fall and many populations shrink across the developing world, governments want to know why their citizens are choosing to have fewer children. The thinking goes that if the obstacles preventing people from having children are removed, then families (and populations) will grow. But a study by Maria Iacovou and Lara Patr?cio Tavares shows that people in the UK don't necessarily have fewer kids than expected because they are economically, socially or even biologically constrained, it's often because they simply change their minds.

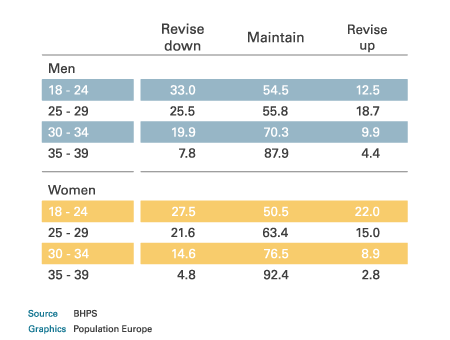

After analysing longitudinal data from the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), the authors conclude that over time many people in the UK change their minds about the desired size of their families (see table 1) – with younger persons (under age of 30) much more likely to revise the number of children they want than older persons (over age of 30).

Table 1 – Over the life-course, people do revise the number of children they want. Percentages of British men and women changing or maintaining their fertility expectations over a five- or six-year period, by age group.

Adjustments include both upward and downward revisions and occur for a variety of reasons. Particularly, the expectations of partners and the experience of parenthood influence future childbearing plans. Additionally, there is quite a defined window of time when individuals make most of their decisions relating to childbirth.

The four-year mark

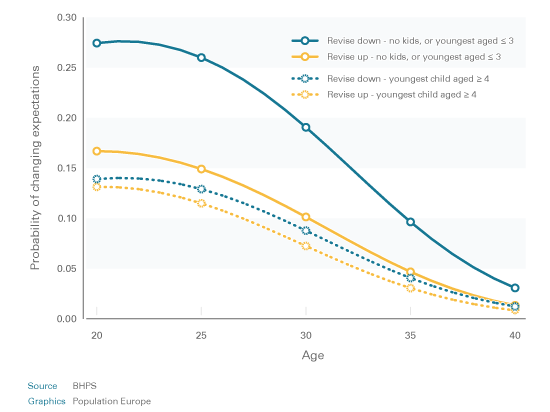

Most people figure out how many children they want during their twenties, before biological clocks or fertility constraints become an issue. This demonstrates that revisions are often based on experience and lifestyle and are not a result of biological limitations. The authors find that there is a window when many of these decisions on family size are made: Most people change their minds before their youngest child reaches four years old (see figure 1).

Figure 1 - Once their children reach four years old, most British women know whether they want to have more kids. The probability of revising fertility expectations either downward or upward falls with age and is lower for those whose youngest child is aged four or older.

The authors propose that this “child-bearing window” occurs because people find out whether they like being parents. If they do, they might decide to have more children. If they don't, they won't. Also, many parents want their children to have at least one sibling who is close in age. So if there is only one child, it is most likely that parents will decide to have another child within four years.

Partners matter

Because this study is based on household data, the authors are able to distil the role partners play on family size. People whose partners expect more children than they do are more likely to revise up. Those whose partners expect fewer children are more likely to revise down. When revising up or down, most partners tend to settle around the cultural norm of two children. The authors also find that people who split up and find new partners are more likely to increase the number of children they plan to have.

A dynamic not a static process

In their analysis, the authors demonstrate how there is push and pull within the greater trends of family size revision. For some people, getting older leads them to decide to have more children. For others, getting older motivates them to have a smaller family. Understanding these smaller upward and downward revisions within the greater trend provides a more nuanced picture of the family planning process.

In the past, many researchers and governments have tried to identify the factors causing low fertility and assumed that simply reversing them would cause fertility to increase. But a number of factors (age, childbirth and the age of the youngest child) will cause some people to decide to have more children and some people to have fewer. This is precisely why the authors recommend looking at the upward and downward revisions separately. In doing this, researchers will better understand why people change their minds when it comes to family size.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.