Fertility trends in the United Kingdom demonstrate both stability and change. Overall, the birth rate has changed less over recent decades than has the timing of those births, which are occurring much later. In a new study, Máire Ní Bhrolcháin, Éva Beaujouan, and Ann Berrington explain how this trend of postponing starting a family can be better understood by examining women's fertility intentions. The authors draw from the responses of women in the United Kingdom’s General Household Survey (GHS) over the period 1991-2007. The respondents report how many children they have, when their children were born, and what their further wishes and future plans for childbearing are. Comparing intentions and average childbearing behaviour, the researchers find that women are often wrong when it comes to predicting when and how many children they will have. They do not precisely plan their first births. And their uncertainty surrounding their childbearing expectations continues well into their thirties.

Inaccurate expectations

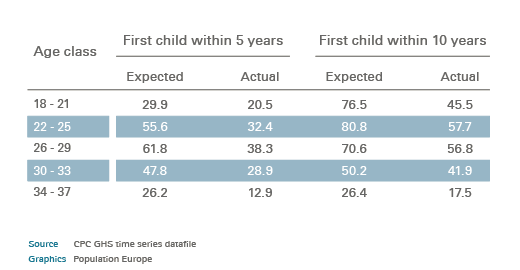

Women in the early 1990s tended to think they would have children sooner than they actually did. The authors show, for example, that while about 55 percent of childless women aged 22-25 in 1991-94 expected to have their first birth within five years, only about 32 percent of the age group did so within that time (table 1). More than 61 percent of childless women aged 26-29 expected to have children within five years, but only about 38 percent actually did.

Figure1: Percentage of childless women in 1991-94 expecting to have their first child within 5 and 10 years, compared with actual proportions proceeding within those durations estimated from fertility histories from 2001-04, by age in 1991-94.

According to the authors, this means that even though most women expect to have children, their actual family building is often approximately, rather than precisely, planned. Therefore they suggest that the interpretation of fertility intentions should be seen more as a reflection of current and recent trends than an indication of future developments.

Family plans delayed not discarded

There is no evidence of a general move away from childbearing per se. For example, from 1991-94 and across all reproductive age groups, between 86 and 89 percent of women in the UK either had or expected to have at least one child. The range in 2005-07 was very similar – from 84 to 91 percent. However, one prevalent fertility trend is that age at first birth is steadily increasing and young women do anticipate this growing delay in childbearing: Childless women aged 18-21 in 1991-92 declared that they expected to have their first birth 6.2 years later, and this figure rose to 6.6 years by 2001-02. Among women aged 22-25, the anticipated wait increased from 4.5 to 4.9 years over the same period. The authors suggest that this postponement is more than just a short-term response to conditions adverse to childbearing. Rather, the whole structure by age of incentives and opportunities for childbearing is changing, resulting in a progressive shift up the age range.

Uncertainty persists

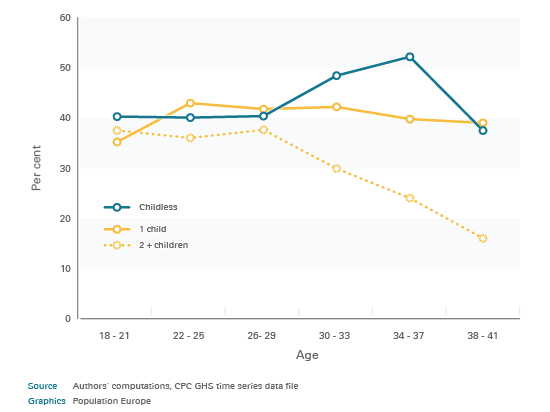

These more flexible concepts of childbearing go along with a high level of uncertainty in family building intentions. Most childless women are uncertain well into their thirties (figure 1). Two fifths of women at ages 38-41 who have fewer than two children and one sixth of those with 2+ still respond without certainty regarding whether or not they will have a (further) child.

Table1 - Uncertainty surrounding childbearing persists well into their thirties for many women in the UK. Percentages uncertain (answers “unstated, don’t know or probably”) in their fertility intention by parity and age, cohorts born 1968-1974.

This indicates that many women see family formation as a fluid rather than a precisely planned process. The authors also note that even if women are certain of their wishes, they may feel that they have limited control over their realisation because of partnership issues. Whether or not women have a suitable partner plays a significant role in their decision to have children, as well as in their expectations about future childbearing.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.