Reconciling work and family is a daily challenge for most Europeans. In the future it might become even more difficult, as shrinking populations will require everybody to work more. In her recent study, Katarina Boye explores the connections between wellbeing, paid work and household duties, and compares the impact that different family policies have on this triangle. The results suggest that work-family conflicts are the big issue yet to be resolved.

Katarina Boye compares the situation of families with at least one under aged child in 18 countries, using data from the European Social Survey (ESS) 2004/2005. She focuses on the amount of time that women and men spend with paid work and housework, and how this correlates with their wellbeing. Special attention is paid to the level of work-family conflict that the respondents of the ESS reported.

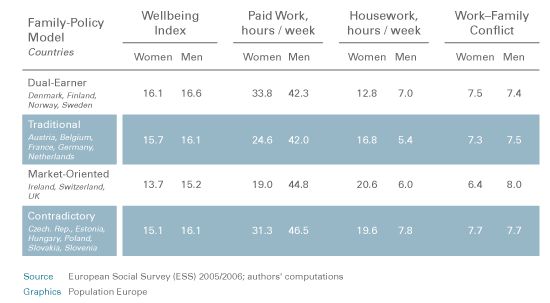

Based on their family-policy approaches, the countries are categorized into four groups: a) the dual-earner model that supports paid work for men and women and treats reproductive work as a state responsibility; b) the traditional model, where reproductive work is treated as a family responsibility and female labour force participation is not especially encouraged; c) the market-orientated model, where the state does not take any responsibilities for reproductive work. It either has to be provided by the family or bought through commercial providers. Paid work for women is encouraged as a necessary source of family income; d) the contradictory model, where women are encouraged to participate in the labour force, but at the same time are treated as mainly responsible for housework (see also Table 1, first column).

Table 1: Mean values for wellbeing, hours of paid work and housework, and level of work-family conflict in all country-groups

Looking at the level of wellbeing, Boye points out that women express significantly lower wellbeing then men across all family-policy models. Only the countries in the dual-earner group provide an exception: Here women and men report almost equal levels of wellbeing, 16.1 and 16.5 (on an index between 0 and 25). These are also the highest mean values of all four country-groups, even though single countries reach even higher values, such as 17.5 for men and 17 and 17.4 for women in Denmark and Switzerland.

The countries in the dual-earner group also show the smallest difference between men and women when it comes to time spent with housework with an average of 13 hours per week for women and 7 for men. It is important to keep in mind that the definition of housework used in this study does not include childcare but :“things done around the home, such as cooking, washing, cleaning care of clothes, shopping, maintenance of property”. Given this rather broad range of activities, there is relatively little variance for men in this field. They spend between 5.4 hours (traditional model) and 8 hours (contradictory model) with housework, whereas for women the variance lies between 12.8 (dual-earner) and 20.6 (market-orientated) hours.

In the market-orientated countries, Boye finds women’s wellbeing declines the more time they spend on housework. A possible reason is that the high dependency on income in these social systems makes the unpaid housework especially unrewarding. The opposite seems to be true for women in traditional model countries: here the association between housework and wellbeing was positive up to a level of 22 hours per week. Homemakers, meaning women who spend little or no time in a paid occupation, do not indicate higher wellbeing then working women in any family-policy model.

However, the basic positive correlation between paid work and wellbeing is significantly threatened by work-family conflicts. The more hours people work, the more likely these problems become, almost irrespective of the dominant family policy model. On an index between 0 (lowest level) and 20 (highest level of conflict), the mean values of all four policy-model groups lay between 6.4 and 8, both for women and men (see table 1, last column). Surprisingly, men in the market-orientated country cluster have the highest level of work-family conflict. Boye suggests, that this correlation is down to the disproportional high number of men working full- and overtime (more than 45 hours per week) to be found in this group.

This research confirms that from a certain workload on work-family conflict seems to be unavoidable and none of the existing family-policies in Europe has made a significant difference yet. The reason might be that individual circumstances matter more then institutional influences. Or it could be that policy makers just have to work harder if they want to encourage Europeans to become more active in both spheres. After all, as Katarina Boye concludes, “it should be a central goal for any welfare state to decrease the strain women and men experience from having children and trying to provide for them.”

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.