Across Europe, statistics show that children from migrant families are less successful in school then other pupils. In a recent article Camilla Borgna and Dalit Contini examine the impact of educational systems and provide explanations beyond language skills and socio-economic background.Using data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) survey, the authors compare results for 17 countries. They focus on second-generation immigrants and their achievements at the end of compulsory schooling, about age 15.

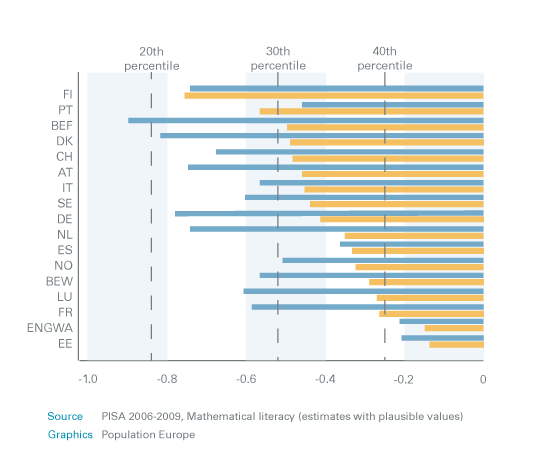

Unlike previous studies, Borgna’s and Contini’s measure is not the average achievement-gap between immigrant and native pupils, but the relative position of immigrant students within the achievement distribution of natives with the same socio-economic background. (see Figure 1)

Figure 1: Underachievement of second-generation immigrants in relation to native pupils (blue bars) and in relation to native pupils with the same socio-economic background (yellow bars)

One of the most striking results from this study shows the existence of educational penalties that don’t operate along the lines of socio-economic background, but specifically affect migrants. According to the authors, “in ten countries, the average second-generation immigrant lies below the 35th percentile of the mathematics achievement distribution of natives with the same socio-economic background.” Similar results were found for reading and science. Borgna and Contini explain that the degree of marginalization that second-generation immigrants face is an important factor for this: The more likely it is that immigrant children end up in “bad schools” the lower their educational achievements. Contrary to common wisdom, such marginalization can not only be produced by a highly stratified school system, as it exists in the German-speaking countries, but also by spatial segregation, or the lack of a national standardization of the education system.

Explaining country differences

The study also shows significant country-differences, which cannot be explained by differences in the composition of the immigrant population, as they were visible even when just comparing the school performance of children with Turkish immigrant mothers. Various researchers have emphasized the importance of pre-schooling and early entry into the educational system when it comes to immigrant children, which can explain the high degree of migrant underachievement found in Finland, where the entry age is 7. Adding to this, the authors of this study present evidence that a combination of late entry and high marginalization creates the high educational penalties that can be seen in Austria, Switzerland, Sweden, Denmark and Portugal.

Countries where school works better for migrant children either have very little marginalization, like Greece, very early entry, like England and Wales, or are characterised by a combination of the two, like Spain, France and Luxembourg.

With regard to early tracking, which has often been blamed for the underachievement of immigrant children, Borgna and Contini point out that this is only associated with severe penalties when coupled with high marginalization.

This Population Digest has been published with financial support from the Progress Programme of the European Union in the framework of the project “Supporting a Partnership for Enhancing Europe’s Capacity to Tackle Demographic and Societal Change”.