Managing undocumented migration is a challenge met with different measures in different countries. Albert Sabater and Andreu Domingo examine recent Spanish approaches to regularisation policy and ask: Can regularisation really be an effective and long-lasting policy tool?

Greedy economy

In general, immigration laws are intended to protect the national labour markets while determining a set of jobs which could be filled by migrants. At the beginning of the 21st century, Spain had in some years the largest net absolute migration in the EU, just behind the US globally. During that time, favourable economic conditions increased the demand for workers in labour-intensive, low-skilled and low-paid economic sectors in Southern Europe, encouraging the arrival of undocumented migrants. As a result, the Spanish government implemented more than one amnesty programme to regularise undocumented migrants. However, as the working permit is limited in duration, some migrants may fall back into irregularity after one or two years.

Old and new schemes

Looking at Spain as an example, Sabater and Domingo have compared the results of the former Normalisation Programme -a “traditional” path to amnesty for irregular migrants-, with the Settlement Programme, the new regulation system that came into effect in 2006. They evaluated the residence and work permit statistics of more than 800,000 foreigners from the Province of Barcelona between 2005 and 2009. The researchers’ aim was to see if migrants whose status was legalised by the different programmes were able to renew their permits or if they lapsed back into irregularity.

In 2005 the largest regularisation programme in Spain, also known as Normalisation, was put into place. More than half a million irregular migrants were granted amnesty nationwide, and 84,000 of whom resided in the Province of Barcelona. The programme had an economic foreground and was promoted as a double-win model: Employers (by avoiding fines) and employees (by obtaining their working permit) would benefit from amnesty. As employers should apply for their employees, students, tourists or people who came to Spain for family reasons and were undocumented could not take part in the Normalisation.

Since 2006 the scheme has changed and undocumented migrants can obtain legal status by the so-called Settlement Programme. By combining the economic and social integration of migrants, the new procedure allows a continuous regularisation of those with economic or familial links to the country. The Labour Settlement scheme is addressed to those individuals who have lived in Spain for at least two years and are able to prove employment for at least one year in advance. Social Settlement allows undocumented foreigners who have lived in the country for at least three years to regularise if they have proven social links with the local community or family networks. In addition, Social Settlement applicants could also provide a work contract proposal for a minimum of one year.

Higher chance to stay with old amnesty programme

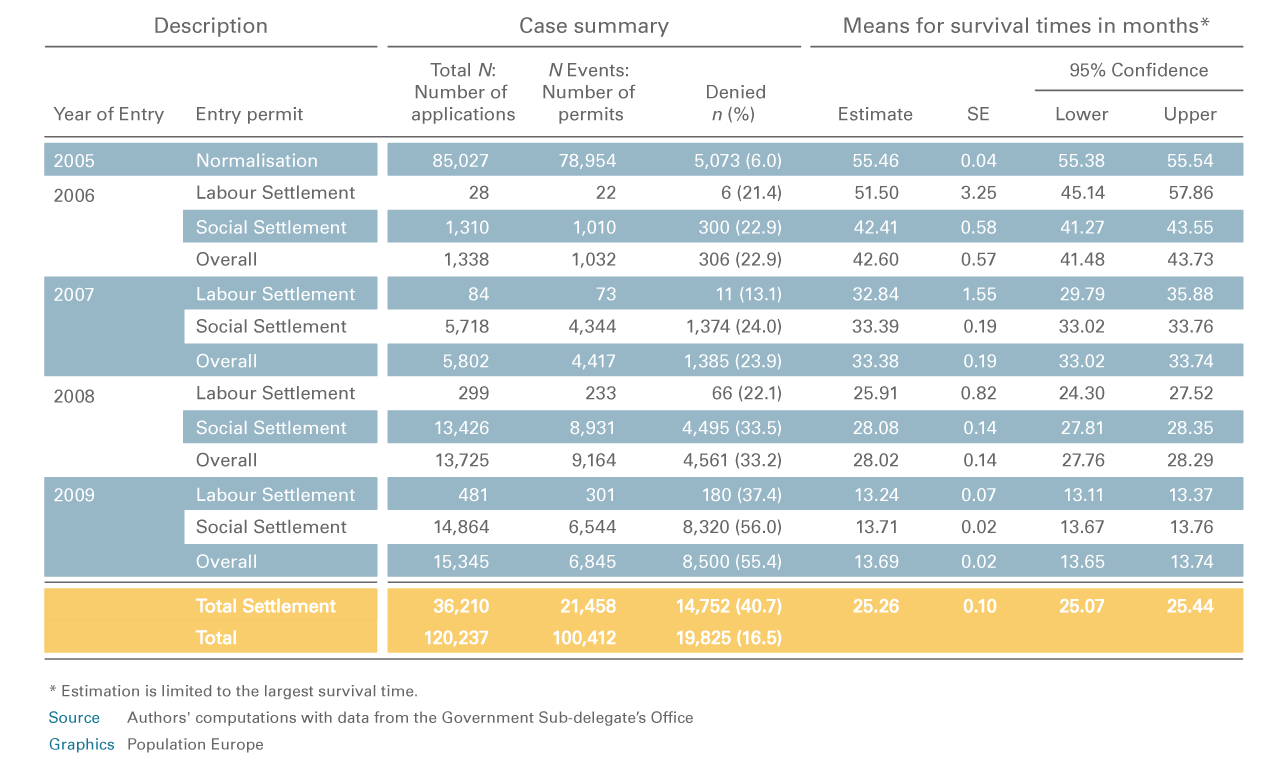

Sabater and Domingo compared programme effectiveness as regards the number of people whose applications were denied. Whereas for the Normalisation Programme just six percent did not receive a permit after the first application, over forty percent of the applicants under the Settlement Programme were rejected between 2006 and 2009 (see Table 1). As all foreigners are supposed to renew their permits, it is interesting to see how long a regularised migrant can keep his or her legal status. For the Normalisation Programme, the researchers find that the elapsed time was 55 months - nearly as long as the five-year period required before being considered a permanent resident. For the beneficiaries of the Settlement Programme, the time is less than half of that. But given that its implementation is more recent, the elapsed time of undocumented migrants within legality is constrained by the year of entry. Clearly, the Settlement Programme becomes, after the Normalisation, a safety net for hard-to-legalise applicants who frequently lapse into irregularity.

Table 1: Mean Survival Times of Normalisation and Settlement by Year of Entry, Province of Barcelona

The table also shows that the number of applications and the percentage of denials rose dramatically over the years. Probably as a reflection of the economic downturn and the reduced need for additional workers, more restrictions were implemented. As a result, 84.8 percent of beneficiaries of Normalisation successfully kept their legal status, whereas nearly a quarter of the Settlement Programme applicants were rejected. While they are expected to then leave the country, many presumably fall back into irregularity.

“Although the Settlement Programme only represented one-third of all applicants, it is responsible for more than two-thirds of the unsuccessful applicants”, the authors point out. However, according to the authors, the new scheme is effective in its consideration of the integration of migrants at local level, while opening new and continuous channels for regularisation. Understanding the pathways towards re- or irregularity provides a powerful tool not only for evaluating how effective migration and regularisation policies are, but for understanding how migrants are affected by integration processes.

This PopDigest is also available in French, Spanish and German.

This volume has been published with financial support of the European Union in the framework of Population Europe.