Anti-gay demonstrations, public votes against the parental rights of same-sex-partnerships - the acceptance of homosexuality still seems to be quite low in some European countries. In a recent study, Judit Tak?cs and Ivett Szalma compared the measurement of homophobia in two large scale longitudinal surveys: the European Values Study (EVS) and the European Social Survey (ESS). Specifically, the authors wondered whether different questions and scales derived from the studies actually measure the same thing in the end. Homophobia has been the subject of measurement in cross-national European Surveys since 1981. It first appeared in the European Values Study (EVS), where the following variable was used: Please tell me whether you think homosexuality can always be justified, never be justified, or something in between. Since then, additional questions have been introduced to measure reactions to homosexuality in the immediate setting.

Different surveys, similar country results

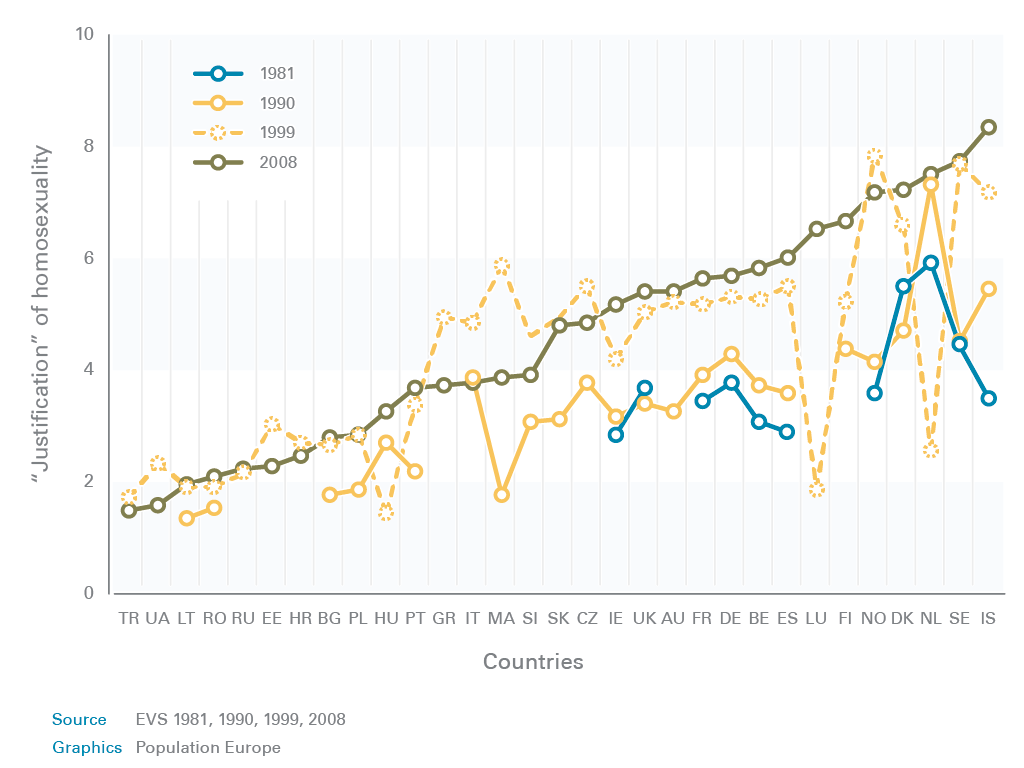

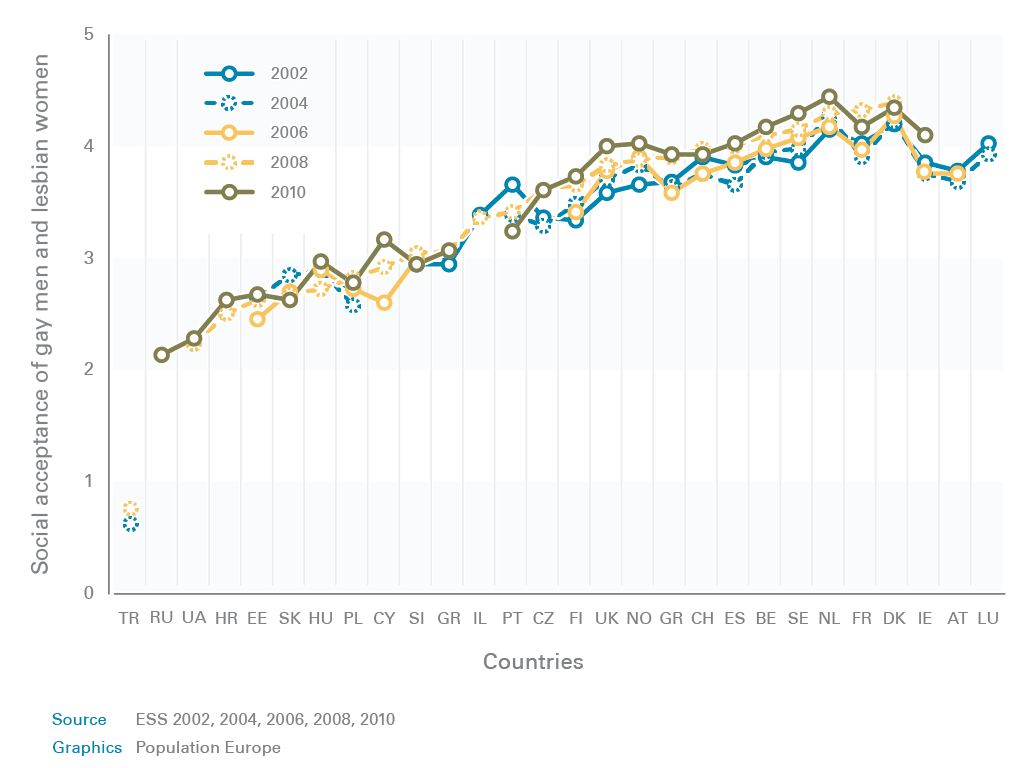

The authors first explore whether both surveys reflect the same trends in homophobic attitudes. They found a very strong correlation among all of the homosexuality-related variables of both surveys. Even though in comparison to the EVS, the ESS reflects shorter term trends, both surveys show a general decrease in homophobic attitudes in most European countries (see graphs 1 and 2).

Graph1: “justification” of homosexuality in Europe between 1981 and 2008

(1= “homosexuality can never be justified”, 10 = “homosexuality can always be justified”)

Graph 2: social acceptance of gay men and lesbian women in Europe between 2002 and 2008

(1= strong disagreement, 5 = strong agreement with the statement “gay men and lesbians should be free to live their own life as they wish”)

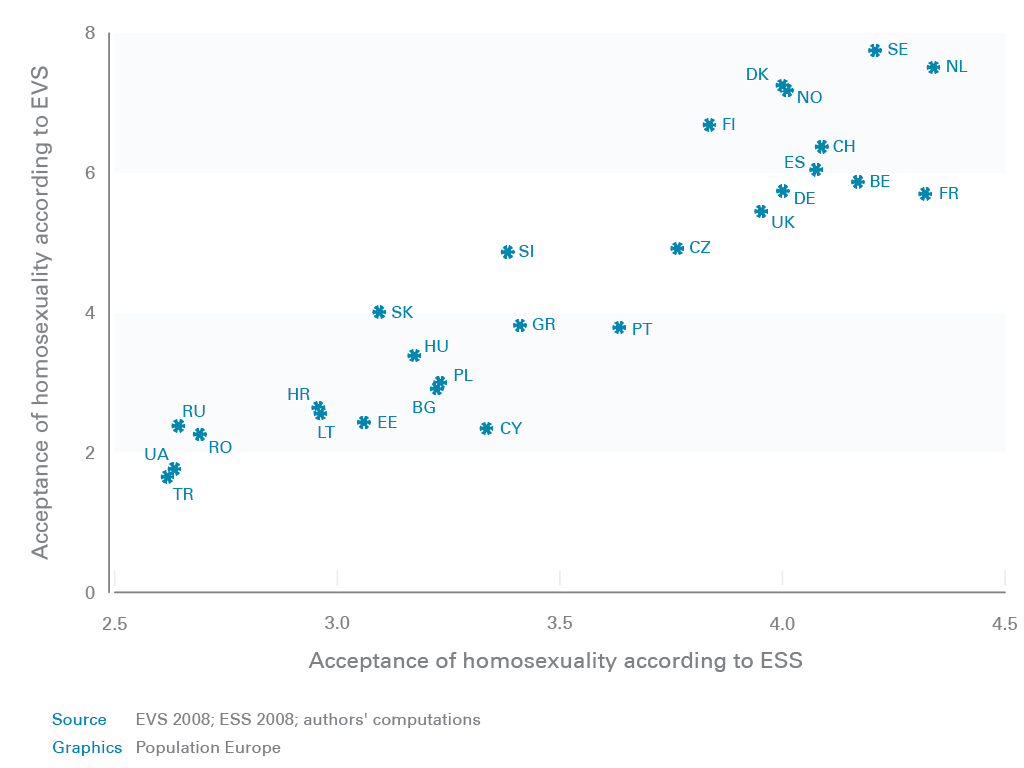

However, country differences are still large. Graph 3 shows the relationship between the variables justification of homosexuality (EVS) and the acceptance of gay men and lesbian women (ESS). Turkey, Ukraine, Russia, Romania, Croatia, Lithuania and Estonia are situated in the most homophobic corner of the graph, while Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway are in the least homophobic one. In addition, the most homophobic countries are also characterized by the most traditional views on gender relations.

Graph 3: relation between the variables “justification” of homosexuality (EVS) and social acceptance of gay men and lesbian women (ESS) in 27 European countries

EVS data on non-preference for homosexual neighbours between 1990 and 1999 reflected a more dynamic decrease of this indicator of homophobia in the post-socialist countries than in the non-post-socialist countries. One has to keep in mind though that the levels of dislike for homosexual neighbours around 1990 originally had been much higher in post-socialist Europe than in most of the Northern and Western European countries. In the first decade of the 21st century the positive trend that could previously be observed in the post-socialist countries has mostly come to a standstill.

Comparing indicators

The study also examines whether attitudes towards same-sex couples were influenced by the same mechanisms according to both surveys. For that, they use the same time frame (2008), the same 27 countries, and the same kind of independent variables from both datasets. They found that there was a significant concordance among countries on all the measurements of homophobia used in both datasets. Women, younger people, those with higher levels of education and people living in larger, more urbanized settlements tended to manifest less homophobic views than others.

Regarding religiosity, respondents who frequently attend religious services and belong to certain denominations (such as the Muslim/Islamic and the Eastern Orthodox) tended to express increased homophobic views. The opposite effect was observed for those who very infrequently attend religious services and do not belong to any denomination. Xenophobic views and traditional gender beliefs also indicate higher levels of homophobia.

“Satisfaction with democracy” was the only individual-level variable, which did not seem to have significant relation to the degree of homophobia – except within the EVS models where those who were not at all satisfied with democracy were more likely to express homophobic views than others.

Concerning future surveys on homophobia the authors see a need for finer measurements that use a more gender-sensitive wording and address more specific topics such as same-sex adoption in greater detail.

*This PopDigest has received funding from the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 320116 for the research project FamiliesAndSocieties.

FamiliesAndSocieties (www.familiesandsocieties.eu) has the aim to investigate the diversity of family forms, relationships and life courses in Europe, to assess the compatibility of existing policies with these changes, and to contribute to evidence-based policy-making. The consortium brings together 25 leading universities and research institutes in 15 European countries and three transnational civil society organizations.