Currently people are living longer lives but not everyone reaches advanced age in good health. This is because health conditions vary among population groups and across territories, giving space to so-called health inequalities. As Benedetta Pongiglione and Albert Sabater confirm in their study, one of the most important features influencing differences in individual health outcomes is socio-economic status: In Europe, overall, highly-educated individuals tend to live longer and in better health than their less-educated counterparts.

At the same time, little is known about how health inequalities in Europe differ among the youngest and oldest members of societies, between men and women, or across regions. In this study, the authors shed further light on the role played by education in determining health conditions in Europe, highlighting three important sources of heterogeneity: First, the way in which the level of education influences health differs over the life course, reaching its maximum in two specific periods; second, there are considerable differences between men and women in those periods of life in which health inequalities are more evident; third, the relationship between education and health and its variations according to age and gender substantially vary across European welfare states.

Your education is important for your health, but depends on your age, gender, and on where you live

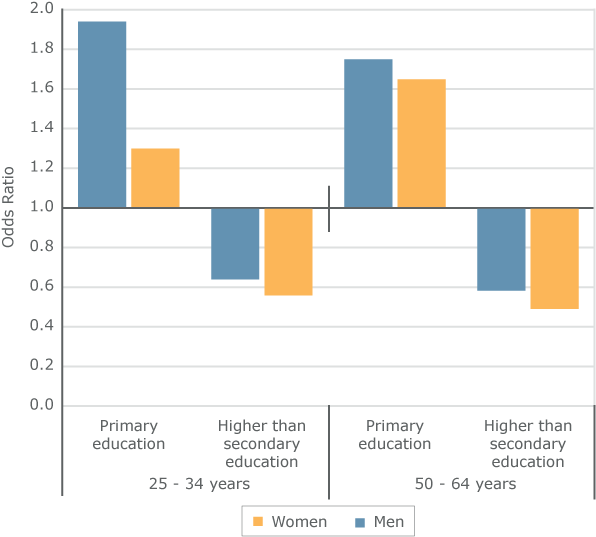

Results indicate that individuals with university degrees appear to be in better health than those with only primary- or secondary-level educations. Nonetheless, the largest differences between perceived health and education level are found in individuals at two different stages of life: those from 25 to 34 years old and those aged 50 to 64. In the youngest age group, having a primary education compared with secondary or tertiary education is more detrimental to the health of men than that of women (Figure 1). This might be due to the higher prevalence (among men) of certain causes of mortality such as accidental injuries, suicide, drug abuse, and sexually transmitted diseases. On the contrary, for those at pre-retirement ages, health inequalities appear to be greater among women than among men (Figure 1), which may be due to the less positive way in which older women assess their own health and their long-term limitations in daily activities.

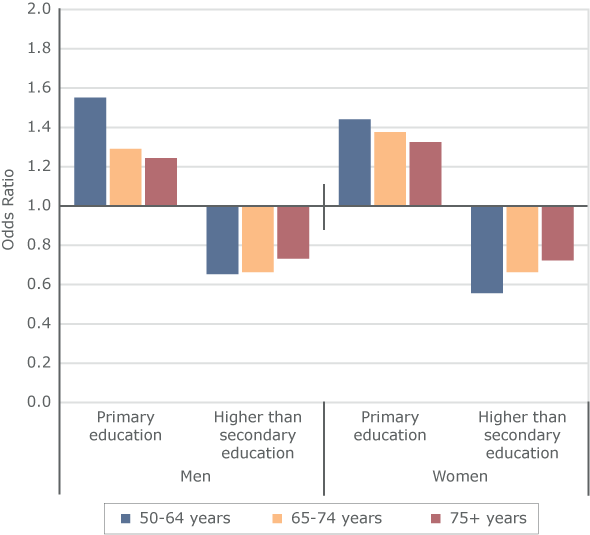

Health differences between people with varying educational levels tend to disappear upon growing old. In fact, health inequalities decrease as age increases, proving that initial inequalities do not grow stronger over the lifetime: After health inequalities have reached their peak at pre-retirement age, they tend to decrease in the latter part of old age (Figure 2). Pongiglione and Sabater also found that the relationship between education and health differ substantially across Europe. Health inequalities in the younger groups (25-49 years old) are greater for both men and women in Eastern Europe (Hungary, Slovenia, Estonia, and Poland), where the protective effect of governmental social policies is weaker. Inequalities are also greater among young women in corporatist states (Switzerland, Netherlands, and Germany), reflecting the difficulties faced by women in these countries when experiencing the duality of work and family life roles.

Figure 1. Odds ratio of having poor self-rated health among the primary-level and the higher than secondary-level educated compared with secondary-level educated, by two age groups (25-34/50-64 years) and gender. Notes: The model controls for demographic variables. Reference category: secondary-level educated.

Figure 2. Odds ratio of having poor self-rated health among the primary-level and the higher than secondary-level educated compared with secondary-level educated, by two age groups and gender. Notes: The model controls for demographic variables and employment and retirement status. Reference category: secondary-level educated.

This Population Digest has been published with financial support from the Progress Programme of the European Union in the framework of the project “Supporting a Partnership for Enhancing Europe’s Capacity to Tackle Demographic and Societal Change”.