by Jakub Bijak

Forced migration, related to armed conflict or persecution is unpredictable [1]. Crises such as the recent one in Syria happen frequently all over the world, forcing many people to flee and seek asylum outside of their home countries.

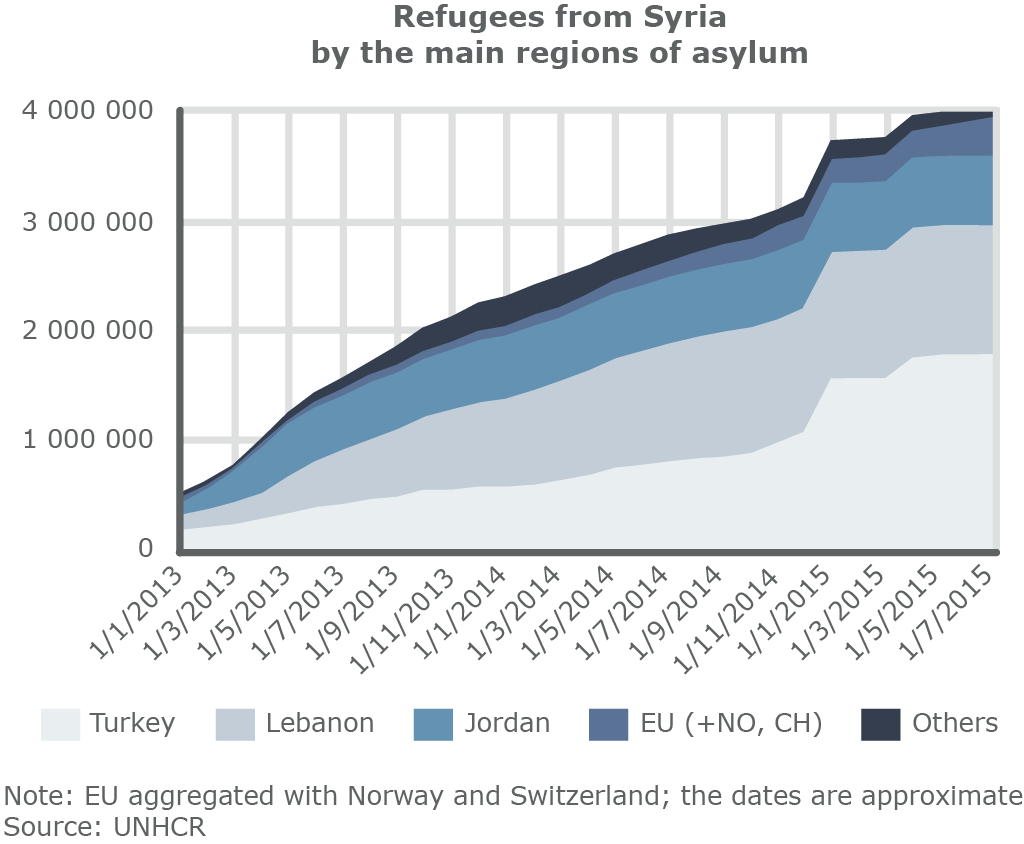

In the Syrian case, over four million refugees have already been registered outside of Syria by October 2015.

Since the adoption of the United Nations Refugee Convention in 1951, and establishing the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), there has been considerable progress in terms of providing the legal framework for international protection of refugees and people seeking asylum. A vast majority of countries are now legally obliged to offer asylum to those who flee the persecution on the grounds of “race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion” (Art. 1 of the Convention). Moreover, “deportation or forcible transfers of population” are recognised as crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Court (Art. 7.1 (d) of the Rome Statute).

Globally, refugees and asylum seekers constitute less than a third of the total number of nearly 60 million people of concern to the UNHCR, a majority of whom are internally displaced within the borders of their home countries. On the other hand, other migrants – people who moved voluntarily for economic, family, education, or other reasons – by far outnumber those who had to flee persecution, armed conflict or violence.

The European Context

The political and social impact of the recent refugee crisis on the European institutions has been very large, to the point of testing the very fundamentals of European integration. The crisis is unfolding at the time when the security threats propagating from Syria to Europe – as the terrorist attacks in Paris on 13 November – become very direct and real.

However, the European side of the crisis needs to be seen in perspective. In particular, the EU countries have not, so far, been the main destinations of Syrian asylum seekers. Most of them remained in the region: nearly a half of the estimated four million refugees from Syria have been registered in Turkey (Figure 1). Even countries like Jordan and Lebanon, which have far smaller capacities to deal with mass humanitarian disasters, have each taken more refugees than the whole EU, despite being much smaller in terms of population and having fewer economic resources to cope with the crisis.

When it comes to Europe, one difficulty is that under the Dublin Regulation, an asylum seeker may only apply for asylum once, in most cases in the first EU country they enter. This measure has been designed to prevent “asylum shopping” in the EU, but in practice it means that the border countries (such as Greece or Hungary) have to process disproportionally high numbers of asylum applications. On the other hand, according to the UNHCR, half of the Syrian refugees who are eventually granted asylum in Europe are ultimately registered in just two countries: Germany and Sweden. The current crisis has demonstrated that the Dublin system is ill-suited to cope with mass humanitarian disasters, and would need to be replaced by a different solution, ideally one coordinated at the EU level.

Figure 1: Syrian refugees, by the main countries and regions of asylum. EU grouped together with Norway and Switzerland. The dates are approximate. Source: UNHCR, 1 October 2015.

Key Challenges

Policies that could alleviate the pressure on the border EU member states would need to involve greater solidarity across Europe. However, in many countries there is not enough political will – the public mood is becoming increasingly anti-immigrant, and this attitude may prevail in shaping the policy responses. Increasing immigration controls only in some well-known locations, such as Calais, will not solve the problem – the human smugglers will find other, riskier routes, and the price of being smuggled to Europe will increase, both in economic terms, as well as in terms of humanitarian cost. Still, given the abuses of the asylum process amidst the crisis, stricter border enforcement across Europe – coordinated by Frontex, the EU borders agency – seems necessary.

At a general level, responding to the crisis brings about substantial challenges. In the short term, the provision of basic humanitarian assistance, aid, and education on a large scale is crucial. In the long term, the UNHCR aims for offering the refugees one of the three “durable solutions”: repatriating to the country of origin; resettling to a third country; or integrating with the host societies. However, while the conflict continues, repatriation is not a real option for many people, while resettlement and integration remain difficult with large numbers of refugees. Any true long term solutions would need to address the conflict first – a diplomatic, as well as a military challenge. Before it happens, there is a danger that temporary solutions – refugee camps, with limited integration and no full civil rights – will prevail.

What are the options?

The crisis has demonstrated that there is an acute need for contingency and crisis planning, in order to deal with the challenges more efficiently [1]. This is similar to responding to natural disasters, such as earthquakes – they cannot be predicted with any reasonable foresight, but some countries (Japan) have excellent crisis management plans and response procedures in place. There are also encouraging examples from other areas: after the recent financial crisis, the international financial regulation authorities put in place measures to create capital buffers for future crises by accumulating funds during the periods of stable economic growth. Achieving this aim in the context of international migration requires a much improved coordination between countries, political and military alliances, international and non-governmental organisations.

Such plans and procedures, however, need to involve creating reserve capacity, which may remain idle for most of the time when it is not needed – like snowploughs at Heathrow Airport during mild winters – but is crucial to help deal with the rare occasion when the crisis impact is really high. A prerequisite for obtaining public mandate for this solution would be an open debate on the merits and price of having such reserves and capabilities. The price is not only economic: in this debate, the difficult questions about trade-offs between liberty and security are unavoidable.

Still, where there’s a will, there’s a way.

[1] Disney G, Wiśniowski A, Forster JJ, Smith PWF and Bijak J (2015): Evaluation of existing migration forecasting methods and models. Report for the Migration Advisory Committee. Southampton: ESRC Centre for Population Change.

Picture Source: Joshua Jackson/unsplash.com

About the author:

Jakub Bijak, Associate Professor in Demography, University of Southampton/UK.