by Athina Vlachantoni

Taking regular care of ageing parents, vulnerable siblings or infirm spouses is an increasingly common experience in our ageing societies.

The provision of unpaid informal care has always been an essential component of social policies in all European countries, and our longer lives are accentuating the need for informal care. But anyone who’s provided such care knows it requires fortitude, endurance, patience, and maybe even a little grit—none of which can be easily summoned in poor health. Naturally, this means that from a policy perspective the health and wellbeing of carers is crucial, for both carer and career.

But disentangling the relationship between informal care provision and the health of carers is a complex matter. Characteristics of the carer, the person being cared for, and the nature of the care being provided all have to be taken into account. Time also matters. Previous cross-sectional research shows that carers are slightly more likely than non-carers to report good health, yet longitudinal analyses show a deterioration in carers’ self-reported physical and mental wellbeing.

So which is it? Do carers have better health than non-carers? Or worse?

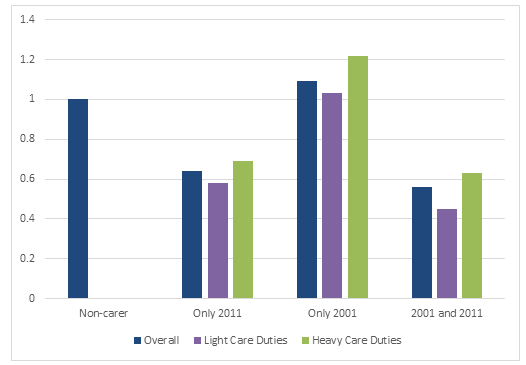

Drawing on data from the Office for National Statistics Longitudinal Study, a 1% sample of the population, we investigated the relationship between care provision and carers’ health ten years later. Specifically, we examined differentials in the self-reported health in 2011 between individuals according to their carer status in 2001 and 2011, controlling for a range of demographic and socio-economic characteristics (like the ones mentioned above). We made the distinction between four groups: carers in only 2001, carers in only 2011, carers in both 2001 and 2011, and non-carers. Within these groups, we also distinguished between “light” (up to 19 hours per week) and “heavy” (20 or more hours per week) care provision.

The results were as complicated as promised (see Figure 1). It turns out, carers in 2011 were less likely to report poor health than non-carers, regardless of whether they had provided care in 2001. In fact, this was true even for those whose care provision was heavy.

Figure 1: Likelihood to report poor health by carers. Source: Office for National Statistics Longitudinal Study.

However, heavy care providers in 2001 who were no longer providing care in 2011 were more likely to report poor health than non-carers. This suggests one of two scenarios: either their care burdens had in fact taken a heavier toll on some than on others, or that less healthy carers were being filtered out. That is, those who continued to provide heavy care after ten years had simply started out in better health.

Unfortunately, as it stands, no causal relationship can be drawn because it is still unclear to what extent care burdens penalised the health of carers who stopped providing care and to what extent they were just less fit to begin with. Nevertheless, by linking data a decade apart, these findings do establish a connection between caring and carers’ health, as well as reaffirm the complexity of that relationship.

What’s clear is that we—policymakers, employers, friends, and family—would do well to bear the wellbeing of our carers in mind, whatever the case.

___________________________________

Further information

The research summarised in this blog post was conducted by Dr Athina Vlachantoni, Dr James Robards, Professor Maria Evandrou and Professor Jane Falkingham at the Centre for Research on Ageing and the ESRC Centre for Population Change, at the University of Southampton, UK. The research was funded as part of the UK’s Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council’s Care Life Cycle project. The permission of the Office for National Statistics to use the Longitudinal Study is gratefully acknowledged, as is the help provided by staff of the Centre for Longitudinal Study Information & User Support (CeLSIUS). CeLSIUS is supported by the ESRC Census of Population Programme (Award Ref: ES/K000365/1). The authors alone are responsible for the interpretation of the data. This work contains statistical data from ONS which is Crown Copyright. The use of the ONS statistical data in this work does not imply the endorsement of the ONS in relation to the interpretation or analysis of the statistical data. This work uses research datasets which may not exactly reproduce National Statistics aggregates. The author is grateful for the assistance of user support officers Julian Buxton, Lorraine Ireland, Shayla Leib, Kevin Lynch, Nicola Rogers, James Warren and the ONS LS Development Team for the extract from the dataset provided, their guidance on the dataset, and clearance of outputs.

About the author:

Athina Vlachantoni, Associate Professor in Gerontology within Social Sciences: Ageing/Gerontology at the University of Southampton/United Kingdom.