Relationships, their typology and meanings have profoundly changed over the past decades in Western societies. These changes constitute an important challenge for welfare states because policies need to take into account new living arrangements in order to support all types of families. Nora Sánchez Gassen and Brienna Perelli-Harris examine the incidence of cohabitation and match it with the associated legal regulation across eleven European countries and Russia in order to quantify the number of couples that fall outside the scope of classical family policies. This study shows how important it is to recognise the diversity of union statuses in welfare state policies to avoid reproducing a potential source of vulnerability among non-traditional families, especially among cohabiters.

Cohabitation is on the rise, but with large variations across countries

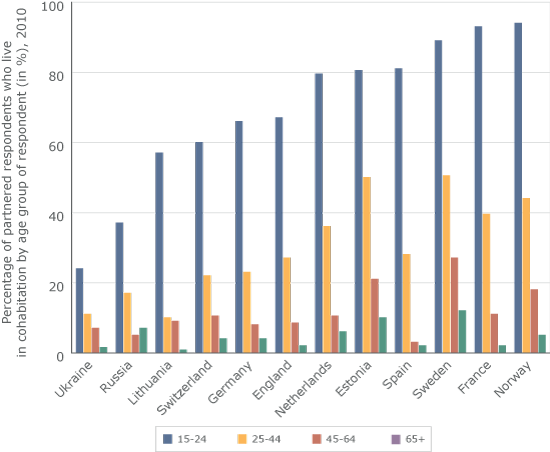

The number of couples living together without getting married has been on the rise, but the extent of its incidence varies greatly across countries (Figure 1). Ukraine, Lithuania and Russia show the lowest incidence of cohabitation among partnered individuals aged 15-44, where less than 20% were cohabiting in 2010. On the other hand, cohabitation is more frequent in Sweden and Estonia where more than half of partnered people under 44 cohabited.

The authors also found that in countries with high levels of cohabitation, such as Sweden, Estonia, Norway and France, most cohabitants aged 15-44 lived in a family with children (Figure 1). Childless cohabitation was more prevalent in other countries, especially in Switzerland.

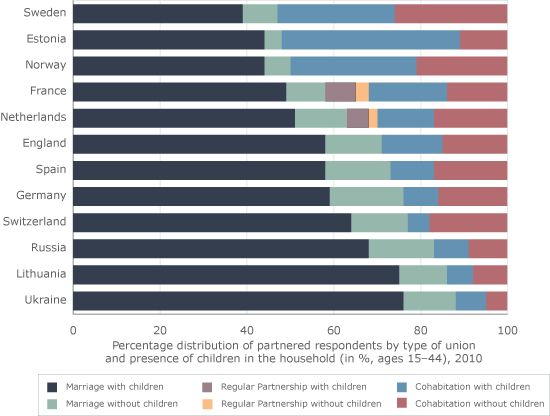

A common feature of cohabitation in Europe concerns its popularity among young people between the ages of 15 to 24 (Figure 2), but there are important cross-country differences. In Norway and France, more than 90% of partnered people of the youngest age group cohabited in 2010; while in Ukraine 24% of partnered young people lived in cohabitation. The proportion of middle-aged cohabitants exceeds 50% only in Sweden and Estonia. Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris state that young adults may be the most affected group in countries with poor legal cohabitation coverage, due to how common this type of union is among this population group.

Cohabitants are not always more protected in countries with higher levels of cohabitation

Sánchez Gassen and Perelli-Harris demonstrate that it is difficult to build a typology of countries across Europe based on the coverage of the legal regulation of cohabitation that was in force in 2010. Countries such as the Netherlands, France, Ukraine, Sweden and Norway had similar rights and responsibilities in some policy areas for cohabitants or registered partners. In other countries, like England, Germany and Spain, the legal status of married spouses and cohabitants differed in most policy areas; while in Estonia, Lithuania, Switzerland and Russia, cohabitants were rarely recognised by law and family policies.

Larger coverage of legal regulation partially matched higher levels of cohabitation in Europe. This is because, overall, cohabitants are more protected by laws and policies in countries where cohabitation is more frequent, such as Sweden, Norway and France. However, important exceptions exist: in Estonia, one of the countries with the highest share of cohabitants, cohabitation was not recognised in most policy areas in 2010. On the contrary, cohabitants were covered by diverse laws in Ukraine even if the country had the lowest incidence of cohabitation of all the countries examined.

The question if and how cohabitation is regulated in Europe is likely to become even more important in the future and affect increasing numbers of couples, since cohabitation rates are rising.

Figure 1. Percentage distribution of partnered respondents by type of union and presence of children in the household (in %, ages 15–44), 2010.

Notes: In France and the Netherlands, data on cohabitation include registered partnerships. Country abbreviations: CH – Switzerland; DE – Germany; EE – Estonia; EN – England; ES – Spain; FR – France; LT – Lithuania; NL – Netherlands; NO – Norway; RU – Russia; SE – Sweden; UA – Ukraine.

Figure 2. Percentage of partnered respondents who live in cohabitation by age group of respondent (in %), 2010.

Notes: In France and the Netherlands, data on cohabitation include registered partnerships. Country abbreviations: CH – Switzerland; DE – Germany; EE – Estonia; EN – England; ES – Spain; FR – France; LT – Lithuania; NL – Netherlands; NO – Norway; RU – Russia; SE – Sweden; UA – Ukraine.

This Population Digest has been published with financial support from the Progress Programme of the European Union in the framework of the project “Supporting a Partnership for Enhancing Europe’s Capacity to Tackle Demographic and Societal Change”.