For the first time in history, the average age of the British population has exceeded 40. In the mid-1970s, it was 34. Thanks to our ever-improving longevity and the ageing of younger migrants, it is estimated the 60+ age group will account for 75% of the UK’s population growth by 2040. British people will be living longer in a population that is itself growing older.

This two-fold demographic transformation will affect how we work, care, learn—and indeed how we live. Housing is one of society’s most important sectors for wellbeing. Across Europe, population ageing will inevitably affect housing supply, demand, and use, which in turn will touch health, lifestyle, and even inheritance.

Policies for home ownership, private renting, and social housing must adapt. The UK Government Office for Science took an important step by commissioning a report on the Future of an Ageing Population.1 It is the product of two and a half years of extensive demographic modelling and scientific evidence reviews and concludes that the success and resilience of the UK in the face of population ageing will be determined by individuals’ ability to cope with the increased risk and responsibility for their ever-lengthening lives—and by the public sector’s ability to coherently support them. Housing policy will be an important part of this.

WHAT TO EXPECT

Population ageing is set to affect housing demand; more homes that meet the needs of older people will be needed, with new ones to be built and existing ones adapted. This means homes with larger, more accessible bathrooms, for example. Downsizing can also help older people manage their household more efficiently.

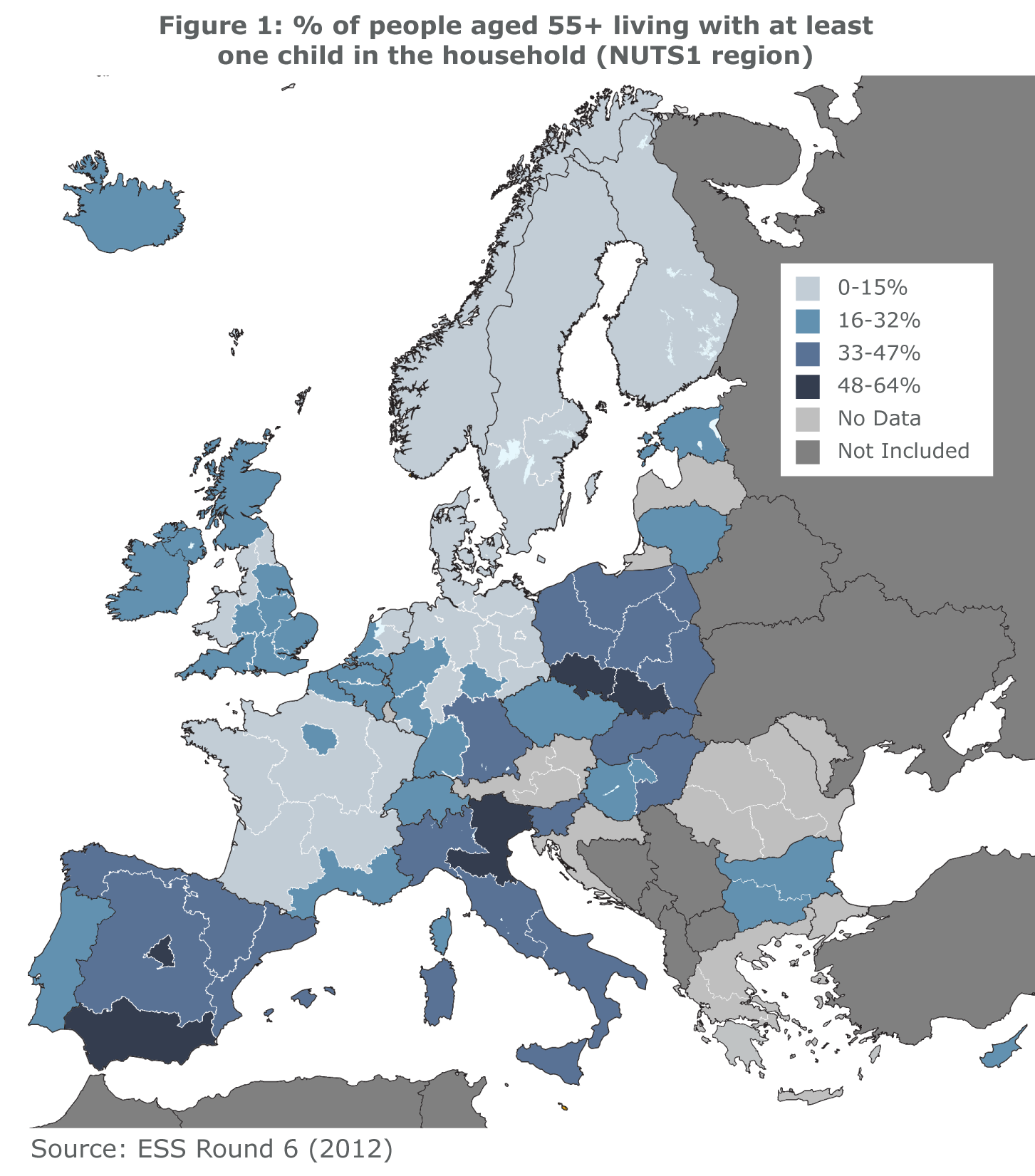

Where downsizing is not the optimal solution, intergenerational living may be. It can improve upward and downward care, prevent social isolation, and reduce costs for families. As the number of generations who are alive at the same time increases, the prevalence of intergenerational living is set to rise. Countries where its share is relatively low, like the UK, could learn from the experience of its European neighbours, like Ireland or Italy, where it is high (Figure 1).

POLICY RESPONSES

Adapting will require a life-course approach. This means knocking down barriers to affordable, adequate housing for both the young, who need to begin building a solid foundation for their financial future, and older people, who have specific needs. Alleviating demand for affordable housing among young families can moderate prices in the wider housing market, ultimately making downsizing or refitting more economically viable. A life-course approach also means accounting for the barriers to intergenerational living, such as the impact of inheritance tax on co-owned properties. Meanwhile, financing and incentives for the construction of new, specialised housing stock will necessarily vary across countries, regions and cities. Measures for facilitating the construction of certain types of housing, like affordable housing, already range from tax credits for developers to the direct deployment of public money. Likewise, there are many models of financing the retrofitting of older homes to make them more energy efficient. These types of targeted interventions will be needed to adapt housing markets for an ageing population as well.

MAKING THE RIGHT CHANGES

The first step, however, is making the right changes in government itself. Population ageing is a cross-cutting phenomenon, connecting issues like health, housing, and work for which policies are often made separately. Housing alone shows they can no longer be addressed in silos. Never in history have we lived so well, but times are changing. Governments across Europe should start preparing now.

Sarah Harper, University of Oxford, United Kingdom