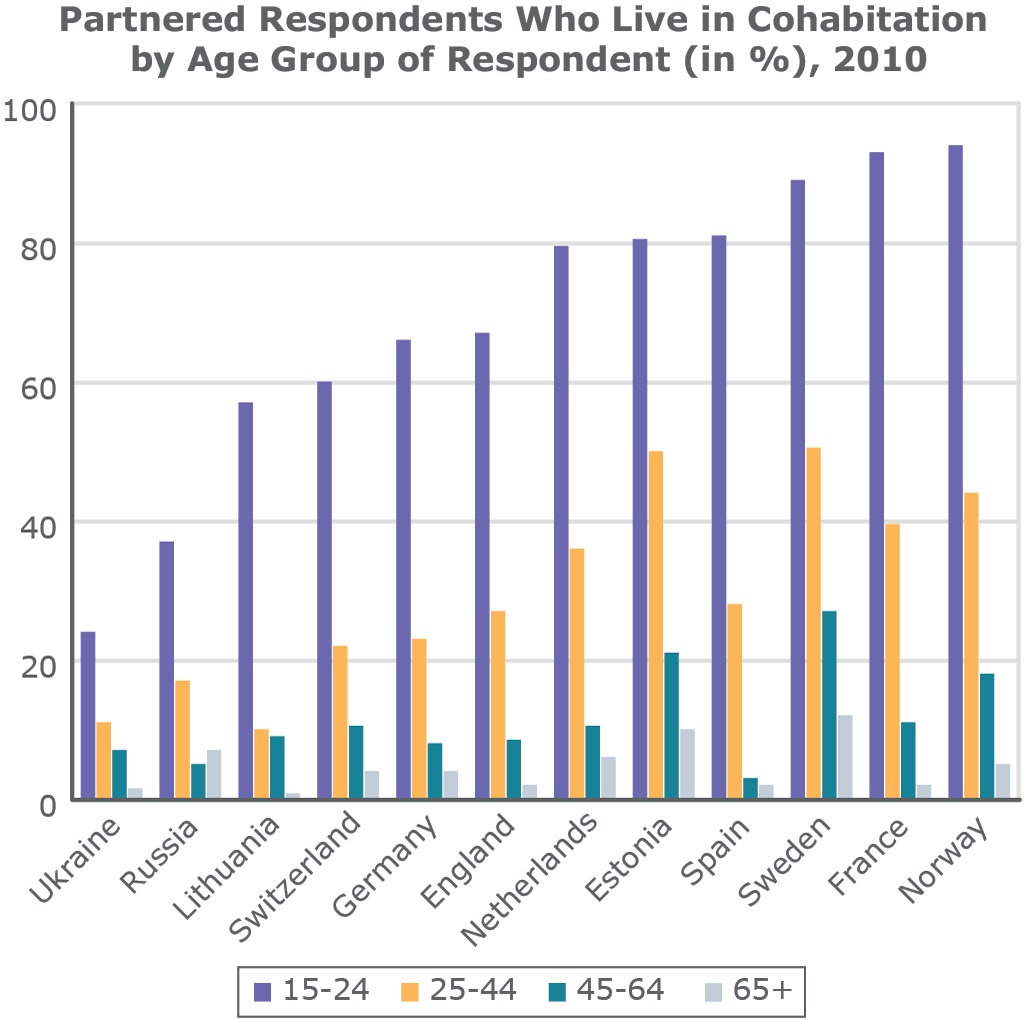

In 2016, thousands of couples across Europe will decide to move in together—without getting married first. It makes sense. Sharing expenses cuts costs in an economy characterized by sluggish wage growth, and living together simply saves time. Plus, cohabitation connotes a certain level of commitment without the legal—and social—obligations that come with marriage. You might call it a baby step. Whatever the case, they won’t be alone. By 2010, nearly 40% of French couples between the ages 25 and 44 had chosen the cohabitation route, registered or unregistered. In Sweden, the figure was just over 50%—a far cry from the near universality of marriage in the 1950s and ‘60s. Childbearing within cohabitation has also become more frequent, with 25 to 30% of all children between 1995 and 2004 being born to cohabiting parents in the UK and the Netherlands. Clearly, cohabitation is not some youthful workaround to traditional rites, but an ever more institutionalised avenue for forming families.

Source: see reference at end of text.

RIPPLE EFFECTS

The trend has given rise to serious policy questions and a plethora of responses. Family law might seem contained enough, but one glance under the hood shows how integrally this policy area is bound up in others—property, inheritance, taxes, social security, leave, custody, and separation come to mind. Making room for cohabitation will ripple through much of a country’s welfare policy sphere, which has historically been based on marriage. But cohabitation’s expansion has motivated policymakers across Europe to have a go.

‘TIL DEATH, ETC., DO US PART

Results of reforms have varied. In the Netherlands, registered partnerships give couples the same rights in terms of alimony and joint assets, to inheritance and widow(er)’s pensions, and to jointly declare income tax. The French PACS (pacte civil de solidarité) is a contract that allows couples to define their property relations and that gives them a number of social and fiscal rights, but these rights are not always as extensive as those for married spouses. In Sweden, an early mover here, no registration is necessary. Cohabiting couples automatically benefit from certain protections in case of separation or death, provided that both partners are unmarried, but coverage is not as comprehensive as in the Netherlands or France. Meanwhile, Spain has left its regions to regulate areas like joint assets and social security for cohabitants. Lithuania hardly makes any provisions at all.

The supply of protections does not necessarily line up with demand. Ukraine offers quite thorough coverage for cohabiting couples despite low levels of cohabitation. Take-up of the Netherlands’ generous protections for registered partnerships has also been modest. Estonia on the other hand has one of the highest levels of cohabitation in Europe, but has moved slowly to provide rights to cohabiting partners in the case of death, separation or unemployment.

BABY STEPS

Clearly, legislating for cohabitation is tricky business—if it weren’t, coverage would simply line up with demand. But legal traditions vary and family policies, strongly related to cultural values, are readily politicised. One way around this is to focus on the wellbeing of the children of cohabiting parents, at least to start. In this way, policymakers can steer clear of prickly questions while simultaneously benefitting from existing research. It would also facilitate the mobility of cohabiting EU couples, who in principle have the right to cross borders to make a living. Establishing thorough cohabitation regimes will be difficult. Governments should still try to keep up. Focusing only on children is not a long term solution, but it’s a start. You might call it a baby step.

Nora Sánchez Gassen, University of Southampton, UK, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Brienna Perelli-Harris, University of Southampton, UK

Reference: Nora Sánchez Gassen and Brienna Perelli-Harris: The increase in cohabitation and the role of union status in family policies: A comparison of 12 European countries. Journal of European Social Policy, Vol. 25 (4), 431-449, 2015.