by Lucie Cerna

Highly skilled people are an indispensable driver of economic growth, competitiveness and innovation. Countries can develop that talent on their own through investment in education and training, but there is a faster way: recruit it from abroad.

Needing to respond swiftly to the challenges of today, we regularly hear politicians talk about competing globally for talent—even in the midst of widespread backlash against migration in any form. More than just talking, many are also taking action.

Others are not, however, and the question is why. In my recent book, Immigration Policies and the Global Competition for Talent, I show that high-skilled immigration policies among OECD countries are varied and diverging, despite all of them sharing the same goal of attracting highly skilled immigrants. OECD countries are all, to some degree, struggling to respond to the pressures created by population ageing, labour and skills shortages, increased global competition and economic integration, the expansion of digitalisation to all areas of work and life, and the need for continued fiscal prudence. Yet they have often pursued very different immigration policies.

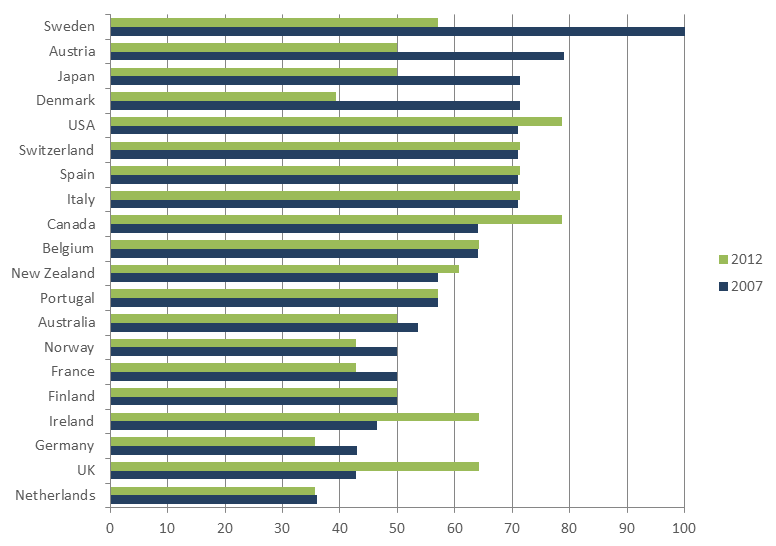

Figure 1 shows the extent of restrictiveness in policies in selected OECD countries in 2007 and 2012. Considerable change has taken place in a five-year period, with some countries liberalising their policies, and others tightening them.

Figure 1: Restrictiveness of high-skilled immigration policies between 2007 and 2012. The length of the bar equates with extent of policy restrictiveness measured by an index of six policy indicators. 100 = Sweden in 2007. All points relate to its base score.

Source: Cerna, Lucie (2016): “The crisis as an opportunity for change? High-skilled immigration policies across Europe”, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42(10):1610-1630.

In fact, changes in immigration policies were significant enough to alter countries’ ranking. In 2007, the most restrictive countries were Sweden, Austria, Japan and Denmark. The most open were the Netherlands, the United Kingdom and Germany. But while the former all underwent considerable liberalisation, the high-skilled immigration policies of the UK became some of the OECD’s most restrictive.

I find that much of the divergence can be explained by the interaction between interests and a country’s institutions. In particular, the extent and nature of collaboration between labour market institutions—such as labour unions or professional associations—and political representatives has played an important role. Differences between those who benefit and those who lose from the introduction of more open policies have mobilised groups to lobby for policies that reflect their interests. Among those benefitting most from high-skilled immigration are employers and domestic low-skilled workers, who do not directly compete with high-skilled immigrants. Conversely, those with the most to lose are domestic high-skilled workers. In each country, all of these groups will have built coalitions to support or oppose greater liberalisation based on the group’s perception of high-skilled immigration as a threat. The extent and nature of these coalitions help to explain why certain countries have opened and others have closed.

By policymakers, high-skilled immigration may be seen as the means to greater economic growth, competitiveness and innovation. However, if they are to gain support for their high-skilled immigration, they must respond to the concerns about the impact of such immigrations policies, real or perceived, on competition for (and access to) jobs, housing, education and healthcare. How well policymakers balance the interests of employers on the one hand and domestic—especially high-skilled—workers on the other will be key to determining the trajectory of reform in high-skilled immigration policies in the years to come.

About the author:

Lucie Cerna, Analyst in the OECD’s Directorate for Education and Skills, Paris/France.

Cerna, Lucie (2016): Immigration Policies and the Global Competition for Talent. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.