by Irene Böckmann

Over the past few decades, things have gotten better. Men have considerably increased the time they spend on childcare and housework, and policymakers across Europe have recognized the value of helping parents reconcile work and care duties. But women still provide a disproportionate amount of care work in European households—between 1.5 and 2.5 times as much as men. This affects women’s labour market opportunities, pensions and, ultimately, wellbeing over the life course. These are the motherhood penalties.

Work-family researchers are examining how gender inequalities within families, in the labour market, and within the workplace interact with each other to reinforce women’s disadvantage vis-à-vis men. They also evaluate how, and to what extent, work-family policies can address these inequalities. It’s becoming clear that tackling motherhood penalties effectively will require coherent action on the part of policymakers, employers, and mothers and fathers at home.

The earnings penalty: a keystone

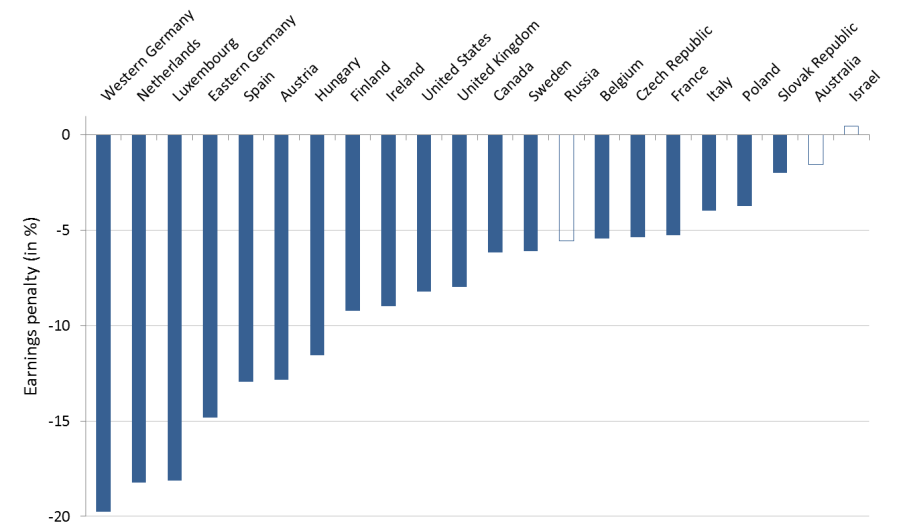

In a recent paper, Michelle Budig, Joya Misra and I wanted to understand how having children affected women’s earnings in the first place and, accordingly, how public policies might mitigate any negative consequences. We found that on average mothers not only earned significantly less than fathers and childless men, but also less than women with no children in the home. Some of these differences can be explained by employment interruptions and the prevalence of part-time work among mothers. But even after taking into account differences in experience, work hours, job characteristics, education and marital status, mothers still earned substantially less than other women in most European countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Earnings Differences between Mothers and Women without Children in the Home.

Source: Budig et al. 2016.

Note: Estimates adjusted for women’s age, education, relationship status, part-time hours, and occupation; based on 2000 data from Cross-National Data Center in Luxembourg. In Russia, Australia and Israel, mothers’ and childless women’s earnings were not statistically different.

Motherhood penalties are not the same everywhere, however. Mothers in Germany, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg incur penalties about three times as large as in the Czech Republic, Belgium and France.

The question is: why?

Public policies

Our findings suggest that mothers incur smaller penalties in countries in which publicly supported childcare services, especially for very young children, are more available. Publicly funded or subsidised childcare shifts some of the care work from families to communities and the state. By supporting non-parental formal childcare, governments can help limit the impact of care work on women’s labour force participation and, consequently, earnings.

Leave entitlements with job protections also allow parents to maintain ties to the labour market, this time while caring for children at home. We find that, all else equal, motherhood penalties tend to be smaller in countries with paid parental leave of moderate length. Very long leave (say, Hungary’s three years) is associated with larger motherhood penalties, mostly for two reasons. First, longer leave can cut into mothers’ work experience. Second, there is the very real risk of incentivising employers, who may perceive long parental leave as an indication of lower job commitment, to avoid hiring or promoting mothers into career-track positions.

However, we also found that mothers in countries with very long leave entitlements incur lower motherhood penalties than mothers in countries with no leave at all, a situation found in the United States.

Fathers

Still, most work-family researchers agree that even the best support for mothers’ employment will not be sufficient to overcome care-work inequalities entirely. Fathers, too, play a central role. Fortunately, more and more European countries are taking steps to encourage fathers to take up a greater share of childcare. A number of countries have followed the “Swedish model” by granting families additional leave if both parents take up at least a minimum length of leave. Such policies have been shown to increase fathers’ take-up of leave, which itself seems to lead to a more equitable distribution of household work after leave ends.

Daddy quotas do not directly address the forces behind men’s low take-up, however, but encourage take-up despite them. Men’s persistent earning’s advantage is partially to blame, as are cultural norms. Many men are also cautious about taking leave because they fear negative repercussions on the job.

Frontline: the workplace

The workplace, where we proudly or reluctantly spend a large part of our working hours, features prominently throughout this field of research. Workplace structures and cultures shape the experiences of women and men who take up parental leave or make use of other measures aimed at improving work-family balance. Research shows that, for example, support from supervisors and workplace cultures that reward task completion over presenteeism and long hours are linked to greater use of parental leave by fathers.

An agenda for rethinking how care is organised and valued in society must be cross-cutting. It must consider the multiple axes of inequality: the division of work between mothers and fathers, job opportunities, income and, closing the circle, the workplace practices that affect the division of care responsibilities at home. It means taking a close look at the availability and quality of childcare services, parental leave policies, and our own expectations as both employees and employers.

It means good faith cooperation between parents, employers, civil society and the state, all of whom surely want to avoid penalising mothers for, well, becoming mothers.

About the author:

Irene Böckmann, Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Toronto/Canada.

Budig, M. J., Misra, J. & I. Boeckmann (2016): Work–Family Policy Trade-Offs for Mothers? Unpacking the Cross-National Variation in Motherhood Earnings Penalties. Work and Occupations 43(2): 119-177.